The Battle of Krasnoi (at Krasny or Krasnoe) unfolded from 15 to 18 November 1812 marking a critical episode in Napoleon‘s arduous retreat from Moscow.[12] Over the course of six skirmishes the Russian forces under field marshal Kutuzov inflicted significant blows upon the remnants of the Grande Armée, already severely weakened by attrition warfare.[13][14] These confrontations, though not escalated into full-scale battles, led to substantial losses for the French due to their depleted weapons and horses.[15]

Throughout the four days of combat, Napoleon attempted to rush his troops, stretched out in a 30 mi (48 km) march, past the parallel-positioned Russian forces along the high road. Despite the Russian army’s superiority in horse and manpower, Kutuzov hesitated to launch a full offensive, according to Mikhail Pokrovsky fearing the risks associated with facing Napoleon head-on.[16][17] Instead, he hoped that hunger, cold and decay in discipline would ultimately wear down the French forces.[18][19][a] This strategy, however, led him in a nearly perpendicular course, placing him amidst of the separated French corps.[22]

On 17 November a pivotal moment occurred when the French Imperial Guard executed an aggressive feint. This maneuver prompted Kutuzov to delay what could have been a decisive final assault,[12] leading him to seek support from both his left and right flanks. This strategic decision allowed Napoleon to successfully withdraw Davout and his corps but it also led to his immediate retreat before the Russians could capture Krasny or block his escape route.[23] Kutusow opted not to commit his entire force against his adversary but instead chose to pursue the French relentlessly, employing both large and small detachments to continually harass and weaken the French army.[24]

Overall, the Battle of Krasnoi inflicted devastating losses upon the French forces, amplifying their already continuous losses during their perilous retreat. Despite the valiant efforts of the Imperial Guard, the confrontation left the French military in dire straits and without supplies and food, further weakening their already battered army.[14][13]

The forces converge on Krasny

Napoleon retreats from Smolensk

Consisting of 100,000 combat-ready yet undersupplied troops, the Grande Armée, departed Moscow on 18 October, aiming to secure winter quarters via an alternative route to Kaluga. Following the loss at the Battle of Maloyaroslavets Kutuzov compelled Napoleon to shift northward, retracing the same ravaged path he had hoped to avoid. Smolensk, situated approximately 360 km (220 mi) to the west, was the nearest French supply depot. Despite fair weather, the three-week march to Smolensk, moving approximately 18 km (11 mi) a day, proved disastrous, subjecting the Grande Armée to challenges like traversing a sparsely populated area with continuous forest, abandoned villages, grappling with demoralization, disciplinary breakdowns, hunger, extensive loss of horses and crucial supplies, as well as persistent harassment from Cossacks and partisans who made it impossible to forage.[25] While sources are not definitive, it’s estimated that he arrived with 37,000 infantry, and 12,000 cavalry and artillery.[26] The situation worsened with the advent of an early and harsh “Russian Winter“,[b] commencing on 5/7 November.[28][29][30]

By 8/9 November, when the French reached Smolensk, the strategic situation in Russia had turned decisively against Napoleon.[31] Merely 40% (37,000) of the remaining Grande Armée was still combat-ready.[32] Concurrent losses on other fronts further exacerbated their dire circumstances. Encircled by encroaching Russian armies that imperiled their retreat, Napoleon recognized the untenability of his position at Smolensk.[c] On 11 November, he ordered Berthier that the new troops should not come to Smolensk but return to Krasny or Orsha. Consequently, the new strategic goal became leading the Grande Armée westward into winter quarters, targeting the area of the extensive French supply depot of Minsk.[33][d]

Having lost contact with Kutuzov over the past two weeks, Napoleon mistakenly assumed that the Russian army had suffered equally due to harsh conditions and was a couple of days behind.[36][37] Underestimating the potential for a Kutuzov-led offensive, Napoleon made the tactical blunder of resuming his retreat. He dispatched the individual corps of the Grande Armée from Smolensk on four successive days, starting on Friday 13 November with the Polish Corps under Zajączek, who replaced the wounded Poniatowski. Next came the Westphalians. Napoleon left on the 14th, at five in the morning, preceded by Mortier with the Legion of the Vistula and Claparède who departed with the captures treasures and baggage wagons;[38][39] Beauharnais left on the next day, Davout on the 16th, and Ney at 2 a.m. on the 17th. This resulted in a fragmented column of disconnected corps, spanning 50 km (31 mi), ill-prepared for a significant battle.[40] In the intervening space between and around these French corps, nearly 40,000 disintegrated troops formed mobs of unarmed, disorganized stragglers. As the soldiers, including the sick, blind and wounded, improvised unconventional methods to withstand the cold, the scene resembled a disordered carnival procession. (Napoleon complained to the Duke of Feltre about the quality of the 180 grain-mills which were sent and distributed.)

A blizzard struck on 14 November, bringing heavy snowfall of approximately 5 ft (1.5 m) and a temperature plummet to -21 °R (= -24°C or -11°F).[41][e] This led to further casualties among men, horses, and the abandonment of artillery.[43] The intense cold enfeebled, first of all, the brain of those whose health had already suffered, especially of those who had had dysentery, but soon, while the cold increased daily, its pernicious effect was noticed in all…actions of the afflicted manifested mental paralysis and the highest degree of apathy.[44] Ostermann-Tolstoy, part of Miloradovich’s avant-guard, shelled Napoleon and his guards, but the assault was repelled.[45] While Miloradovich desired to attack, he was not granted permission by Kutuzov. Meanwhile, Claparède and the Vistula-legion arrived at Krasny since August occupied by a small French battalion. They were expelled by Ozharovsky’s flying column.[46]

In the afternoon of 15 November, Napoleon himself arrived at Krasny accompanied by his 12,000-strong Imperial Guard.[47] He planned to await the arrival of the troops of Eugène, Davout and Ney over the next several days before recommencing the retreat.[f]

Kutuzov’s southern march

During the same period, the main Russian army under Kutuzov followed the French on a parallel southern road.[48] This route passed through Medyn and Yelnya,[49] the latter became a significant center for the partisan movement. Unlike the Grande Armée, the main Russian army approached Krasny in a much less weakened state,[50] but still had to contend with the same, extreme weather conditions and scarcity of food. Kutuzov promoted an easy retreat for the French army and initially forbade his generals to cut off their retreat.[51] General Bennigsen, who disagreed, was sent back to Kaluga on the 15th?

Due to outdated intelligence reports, Kutuzov somehow believed that only one-third of the French army had passed from Smolensk to Krasny with the remainder of Napoleon’s forces marching much farther to the north or still at Smolensk.[52][g] On this basis, Kutuzov accepted a plan proposed by his staff officer, Colonel Toll, to march on Krasny to destroy what was believed to be an isolated Napoleon.[3]

The Russian position at Krasny began forming on 15 November, when the 3,500-strong flying advance guard of Adam Ozharovsky took possession of the town, located in the Pale of Settlement, and destroyed magazines and stock before the French arrived.[3][54] On the same day, the 18,000 troops of Miloradovich established a strong position, across the high road about 4 km (2.5 mi) before Krasny. This movement effectively separated Eugene, Davoust, and Ney from the Emperor.[55][56] On 16 November Kutuzov’s 35,000-strong main force slowly approached from the south,[57] and halted 5 km from the main road to Krasny. Another 20,000 Cossack irregulars, operating mostly in small bands, supplemented the main army by harassing the French at all points along the long road to Krasny. In the first skirmishes at Krasny, the French still showed stubborn resistance and desperate courage.

Seeing that all our Asiatic attacks were collapsing against the closed formation of the European one, I decided to send the Chechen regiment forward in the evening to break down the bridges on the way to Krasny, block up the road, and try in every possible way to block the enemy’s march; but with all our forces, encircling right and left and crossing the road in front, we exchanged fire with they were, so to speak, the vanguard of the vanguard of the French army.[58]

In total, Kutuzov commanded a force of 50,000 to 60,000 regular troops, which included a substantial cavalry unit and around 50/200 cannon, some transported on sledges.[59][47] Kutuzov’s forces were organized into two columns. The larger contingent, under the leadership of General Tormasov, formed the left flank and maneuvered around Krasny so Napoleon could not withdraw.[60] Meanwhile, the second column, led by Golitsyn and his brother-in-law Stroganov, held the army’s center and launched an attack on Krasny. Miloradovich’s position anchored the Russian right flank, controlling a vital road to Krasny. This road required the French army to cross a stream within a gully. Despite Miloradovich’s pivotal role, he left his strategic position to aid Golitsyn against the Young Guard.[61][10] Consequently, Davout managed to successfully cross the Losvinka brook, albeit at the cost of his rearguard’s sacrifice.[h]

15 November: the rout of Ozharovsky

Outside Smolensk, leaving the floodplain of the Dniepr, there is a steep slope passing into a long descent, slightly undulating until Krasny. The rear of the Imperial Guard was harassed by the Cossacks of Orlov-Denisov, who captured 1,300 soldiers, 400 carts and 1,000 horses. Near Merlino, around noon, the Imperial Guard, marched past Miloradovich’s troops, who were positioned left of the road, backed by a forest.[55] Impressed by the order and composure of the elite guardsmen, Miloradovich had orders from Kutuzov not to attack the flanks, and settled instead for bombarding the French at extreme range.[62] The Russian cannon fire inflicted little damage on the large corps of Guards which continued moving toward Krasny.[62]

As Napoleon and the Imperial Old Guard approached, it was fired upon by Ozharovsky and Russian infantry and artillery. A surprised army did not expect that they had been overtaken and could be attacked from the front. The eyewitness description of this encounter by the partisan leader Davidov, which eloquently portrays the comportment of the Old Guard, forming a “fortress-like square”,[63] has become one of the most often quoted in the histories of the 1812 war:

…after midday, we sighted the Old Guard, with Napoleon riding in their midst… the enemy troops, sighting our unruly force, got their muskets at the ready and proudly continued on their way without hurrying their step… Like blocks of granite, they remained invulnerable… I shall never forget the unhurried step and awesome resolution of these soldiers, for whom the threat of death was a daily and familiar experience. With their tall bearskin caps, blue uniforms, white belts, red plumes, and epaulettes, they looked like poppies on the snow-covered battlefield… Column followed upon column, dispersing us with musket fire and ridiculing our useless display of chivalry… the Imperial Guard with Napoleon ploughed through our Cossacks like a 100-gun ship through fishing skiffs.[64][i]

Before dusk, Napoleon entered Krasny. He planned to remain so that Eugene, Davout and Ney could catch up with him. However, part of this small town was set on fire after the Old Guard took shelter in the monastery, barns and houses.[66] The streets were filled with soldiers and there was not much to eat or drink. As there was not enough room the Young Guard camped east, outside the town without any shelter against the cold. To keep his men busy Napoleon decided in the late evening to force the withdrawal of Ozharovsky’s Cossacks from the Losvinka.[67]

Recognizing that Ozharovsky’s position was dangerously isolated from Kutuzov’s main army, Napoleon dispatched the Young Guard under General Claparède on a surprise attack against the Russian encampment, which was not protected by pickets. The operation against their center was first entrusted to General Rapp,[68] but at the last moment, he was replaced with General Roguet; the Guardsmen were divided into three columns. Shortly after midnight, it was two o’clock when the movement began on Ozharovsky’s force. They began a silent advance although the snow was up to their knees. (The Old Guard stayed behind and did not fight.) The Young Guard (under Delaborde) launched a counterattack and drove Ozharovski’s detachment back from the brook. In the ensuing combat, the Russians were taken by surprise during their sleep and, despite their fierce resistance, were routed. As many as half of Ozharovsky’s troops were killed with bayonets or captured, and the remainder threw their weapons in a pond and fled. Lacking cavalry, Roguet was unable to pursue Ozharovsky’s remaining troops.[69] On the same evening Alexander Seslavin captured Lyady; he destroyed two warehouses and took many prisoners, according to Davidov. According to sergeant Bourgogne:

On the evening of our arrival the Russian army surrounded us, in front, to the right, left and from behind. General Roguet received the order to attack during the night, with a party of Guard regiments of fusiliers-chasseurs, grenadiers, voltigeurs and tirailleurs.

I have omitted to say that, as the head of our column charged into the Russian camp, we passed several hundred Russians stretched on the snow; we believed them to be dead or dangerously wounded. These men now jumped up and fired on us from behind, so that we had to make a demi-tour to defend ourselves. Unluckily for them, a battalion in the rear came up behind, so that they were taken between two fires, and in five minutes not one was left alive. This was a stratagem the Russians often employed, but this time it was not successful.

We went through the Russian camp and reached the village. We forced the enemy to throw a part of their artillery into a lake there and then found that a great number of foot soldiers had filled the houses, which were partly in flames. We now fought desperately hand-to-hand. The slaughter was terrible, and each man fought by himself for himself.

As a result of this murdering combat, the Russians withdrew from their positions, without moving away, and we stood on the field of battle throughout the day.[70]

Golitzin therefore decided to await Miloradovich’s co-operation before pressing his advance.[71]

16 November: the defeat of Eugène

Miloradovich attacks

Jean-François Boulart described the situation when he arrived at the Losvinka on the previous evening:

A little further on, there was a ravine that had to be crossed on a bridge, beyond which immediately lay a line of heights to climb. This passage became the scene of a tremendous congestion of vehicles of all kinds. After three hours of a halt, I was informed that all movement of vehicles, all passage on the bridge had ceased, and the congestion was impenetrable. Finally, after a thousand hardships, the head of the column reached the bridge, which still needed to be cleared, and penetrated to the head of the congestion. The path was clear, indeed, but it immediately began to ascend rapidly, and the ground was icy. One hour before daybreak, all my artillery was at the top.[72]

In the afternoon of 16 November, the Italian corps of Viceroy Beauharnais arrived at gully.[j] On the other side Mikhail Miloradovich put up a barrier next to and across the road,[74] by a detachment of infantry, light cavalry and half of the Russian artillery.[75][76] On a beautiful plateau according to Roguet.

The Krasnoy defile was an excellent place to stop a retreating army. In a deep, steep-sided gully, a steep road, made even more difficult by the icy conditions, led to a narrow bridge. A large number of carriages and baggage piled up on the bridge. The infantry marched on, hampered by the other disorganized arms. The Emperor stepped back from the road, called together the officers and non-commissioned officers of the old guard, and told them he would not see the bonnets of his Grenadiers amid of such disorder: I am counting on you as you can count on me to accomplish great deeds.[77]

On this day, the situation took a turn for the worse for the French. The whole day was spent in waiting for the three corps that had left Smolensk when Kutuzov’s forces closed in on the main road. Fyodor Petrovich Uvarov succeeded to cut off Eugène de Beauharnais and his IV corps from the rest of the army but refrained from launching an attack on the rear with his cavalry. In contrast, Miloradovich’s troops dealt a severe blow to Prince Eugène who refused to surrender.[78][79] In this skirmish, his Italian Corps lost one-third of its original strength, along with its baggage train and artillery at the Losvinka.[k] Reduced to only 3,500 combatants, without any cannons or supplies,[60] Eugène was left with no choice but to wait until nightfall and then find an alternate route around the Russian forces.[80] Eugène fooled the Russian general by attacking his army on the left flank but managed to escape with part of his soldiers to the right.[78] This escape was partly due to Kutuzov’s decision to prevent the skirmish from escalating into a full-scale battle, much to the surprise of both Russian and French forces.[81][82]

Kutuzov at Zhuli

Earlier that day, Kutuzov’s main army finally arrived within 26 km (16 mi) of Krasny, taking up positions around the hamlets of Novoselye and Zhuli. Despite being in a favorable position to attack the French, Kutuzov hesitated. He opted for a day of rest for his troops, delaying any decisive action.

In the evening, Kutuzov faced pressure from the disagreeing junior generals, especially Wilson, urging him to launch a decisive attack against Napoleon. The Russians were able to surround Napoleon and overwhelm him by their sheer superior numbers.[84] However, he remained cautious and only planned for an offensive. He forbade his commanders from executing it until daylight. The Russian battle plan involved a three-pronged attack on Krasny: Miloradovich was to hold his strategic position on the hill, blocking the advance of Davout and Ney. The main army would split into two groups: Golitsyn would lead 15,000 troops and halt on the right bank of the Losvinka, in full sight of Krasny,[85] while Tormasov commanded 20,000 troops tasked with encircling Krasny and cutting off the French retreat route to Orsha.[86] Ozharovsky’s flying column, weakened after their defeat by the Young Guard, would operate independently west of Krasny. The remnants of Eugène’s Westphalian Corps were incapable of taking any part in the action, when they arrived late in the evening. Napoleon ordered it to defile on the road to Orsha as Krasny was full with soldiers.

However, at some point, Kutuzov received information from prisoners (quartermaster Puybusque and his son) that Napoleon intended to remain in Krasny and wait for Ney and not withdraw as Kutuzov had anticipated upon the arrival of Davout. This revelation caused Kutuzov to reconsider the planned offensive after Ozharovsky’s defeat, as reported by Nafziger and Gourgaud.[87][88]

17 November: Napoleon’s bold maneuver

Peril for Davout

The day began at 3:00 a.m. when Davout’s I Corps set out towards Krasny upon receiving troubling reports of Eugene’s defeat the previous day. Originally, Davout had intended to wait for Ney’s III Corps, which was still at Smolensk, to catch up.[89] However, sensing a relatively clear path, he approached the Losvinka brook around nine in the morning.

Unfortunately for Davout, Miloradovich, with Kutuzov’s permission, initiated a sudden and intense artillery barrage on Davout’s corps. This unexpected attack instilled panic among the French troops, resulting to a hasty retreat from the road and leaving the rear guard (Dutch 33rd Regiment) on the verge of annihilation. Davout’s corps suffered severe casualties, with only 4,000 men remaining.[90]

An intriguing, though poorly documented incident occurred near the Losvinka when the rear end of the I Corps baggage train, including Davout’s jammed carriages, fell into the hands of the Cossacks.[91] Among the items seized by the Russians were Davout’s war chest, numerous maps depicting the Middle East, Central Asia, and India, his Marshal baton and an item of significance – a concept or copy of the treaty – in the peace negotiations with Tsar Alexander;[92] some sources even mention a substantial sum of (forged) money as part of the haul.[93][94] The exact location of this incident, whether it occurred east of Krasny in the morning or west of Krasny in the afternoon, remains unclear.

Napoleon Ordering the Guard’s Advance

On the 17th, at daybreak, it was announced that the Emperor, at the head of the Guard, was going to move towards the defile in question to dislodge the Russians and open the passage for the corps that were stopped there in an awkward position. Four batteries of the Guard were requested. During the three or four hours that the affair lasted, I was far from remaining idle and at rest. The retreat was anticipated; it was necessary to get rid of everything that could not be taken along because the number of my horses, already greatly diminished, had suffered further losses by the obligation to complete the teams of the batteries that were going into battle, and it was necessary to sacrifice part of the equipment. The intensity of the noise, aided by beautiful freezing weather, remained the same for a long time, indicating a great tenacity of resistance; but at the same time, skirmishes could be heard on our left, announcing that we were being outflanked on that side. We were all in the greatest anxiety, which was further increased by the disorderly movement of troops and wagons covering the road and stretching into the rear; it was a true spectacle of desolation and one of the most distressing scenes. – General Bon Boulart[95]

Napoleon, fully aware of the grave danger confronting the Grande Armée, faced a critical decision. Waiting for Ney in Krasny was no longer a viable option; any determined attack by Kutuzov could spell disaster for the entire army. Furthermore, the starving French troops urgently needed to reach their closest supply source, 70 km (43 mi) west at Orsha, before the Russians could capture the town.[96]

In this critical moment, Napoleon’s “sense of initiative” resurfaced, marking the first time in weeks. As Caulaincourt’s described it: “This turn of events, which upset all the Emperor’s calculations… would have overwhelmed any other general. But the Emperor was stronger than adversity, and became the more stubborn as danger seemed more imminent.”[96]

Before daylight broke, Napoleon prepared his Imperial Guard for a bold feint against Golitsyn, hoping that this unexpected maneuver would dissuade the Russians from launching an assault on Davout. The Guardsmen were organized into attack columns, and the remaining artillery of the Grande Armée was readied for combat.[97] Napoleon’s strategy aimed to delay the Russians long enough to gather the forces of Davout and Ney, allowing the retreat to resume before Kutuzov could launch an attack or attempt to outflank him on the route to Orsha.[97]

The Imperial Guard demonstrates its strength

At 2:00 a.m., four regiments of the Imperial Guards departed from Krasny to secure the terrain immediately to the east and southeast of the town.[99][100][l] This marked a significant moment as Napoleon deployed the Old Guard, consisting of 5,000 exceptionally tall and well-trained men, to confront the Cossacks who had blocked the road near the Losvinka. Napoleon himself chose the role of a general leading the Young Guards, relinquishing his position as the supreme commander of the army.

I have played the Emperor long enough! It is time to play general![m]

The Guardsmen found themselves facing Russian infantry columns, bolstered by imposing artillery batteries commanded by Golitsyn and Stroganov. As Ségur poetically put it: “Russian battalions and batteries barred the horizon on all three sides—in front, on our right, and behind us”[63]

Kutuzov, lacking comprehensive information, reacted hesitantly to Napoleon’s presence and audacious maneuver with the Imperial Guard. He ordered Miloradovich to assist, delayed Tormasov for three hours and eventually abandoned the planned offensive, despite the Russians’ clear numerical advantage.[n]

Napoleon did not retreat, but decided to attack with the Young Guards in order to force Kutuzov to draw Miloradovich to him.[103] At some time Miloradovich moved south to reinforce Golitsyn against the Young Guards.[104][61] When Miloradovich left his commanding position on the hill to join the battle, he left behind a small detachment of Cossacks.[105] This allowed Davout to successfully fight his way through and enter Krasny.[39][106] The Guard’s audacious feint rescued Davout’s corps from potential annihilation.[107]

Action at the Losvinka brook

At nine in the morning, Davout’s rear guard, the 33rd regiment, formed a defensive square at the Losvinka. It was on this particular day that limited close-quarters combat unfolded during the morning and early afternoon. The Young Guard initiated an attack to provide cover for Davout’s crossing of the Losvinka further north.[110]

Uvarovo, located just a half-hour’s walk from Krasny, was initially held by two battalions of Golitsyn’s infantry, serving as a fragile forward outpost ahead of the main Russian army. However, the Russians were eventually forced to withdraw from Uvarovo. Stroganov responded with a devastating artillery barrage that inflicted heavy casualties on the Young Guardsmen.[111]

Kutuzov ordered Miloradovich to reposition his forces, linking up with Golitsyn’s lines and concentrating their strength behind Golitsyn’s position.[111] This maneuver prevented Miloradovich from completing the destruction of Davout’s troops.[112]

As Davout’s troops continued their westward movement, they were relentlessly harassed by Cossacks, and Russian artillery under Stroganov pounded Davout’s corps with grapeshot, causing devastating casualties. Although Davout’s personal baggage train suffered significant losses, a considerable number of his infantrymen managed to rally in Krasny.[113] Once Davout and Mortier established communication, Napoleon initiated his retreat upon Lyady with the Old Guard. However, the Dutch 3rd Regiment Grenadiers and Red Lancers were left to support Mortier and engage the Russians.[114][o]

The rearguard of Davout’s corps, consisting of the chasseurs from the Dutch 33rd Regiment, faced relentless attacks from Cossacks, cuirassiers, and infantry, becoming encircled and running low on ammunition. The regiment formed defensive squares and successfully repelled the initial attacks.[79] However, during the third Russian assault, they became trapped leading to the demise of the entire regiment, with only 75 men surviving.[118][119] This loss marked the end of the battle of Krasnoi as noted by Clausewitz and Georges de Chambray.[120][121]

Around 11:00 a.m., Napoleon received alarming intelligence reports indicating that Tormasov’s troops were preparing to march west of Krasny.[p] This, forced Napoleon to reconsider his initial plan of keeping Kutuzov occupied until Ney’s III Corps could reach Krasny. The risk of being encircled and defeated by Kutuzov’s forces was too great. Napoleon made a crucial decision to order the Old Guard to fall back on Krasny and follow him in a westward march towards Lyady. Meanwhile, the exhausted Young Guard would hold their ground at the Losvinka. Napoleon’s choice was not an easy one, as described in the words of Segur:

So the 1st Corps was saved; but we also learned that our rear guard was at the brink of collapse in Krasny, that Ney probably hadn’t left Smolensk yet. We had to give up the idea of waiting for him. Napoleon hesitated, finding it difficult to make this significant sacrifice. But when all seemed lost, he finally decided. He called Mortier to his side, grasped his hand kindly, and said, ‘There is no time to lose! The enemy is breaking through from all sides. Kutuzov may reach Lyady, even Orsha and the last bend of the Dnieper before me. I must move swiftly with the Old Guard to secure that passage. Davout will relieve you. Together you must hold on at Krasny until nightfall. Then you shall rejoin me.’ Heavy-hearted, knowing he had to abandon the unfortunate Ney, he slowly withdrew from the battlefield, passing through Krasny where he briefly halted, before cutting his way through to Lyady.[124]

The Young Guard’s ability to withstand the Russian onslaught was rapidly deteriorating, and Mortier wisely ordered a retreat before the remaining troops were surrounded and annihilated.[87] With precision, the Guardsmen executed an about face and marched back to Krasny, enduring a final devastating barrage of Russian cannon fire as they retreated at 2:00 p.m.[125] The toll was staggering, with only 3,000 survivors remaining from the Young Guard’s original 6,000 troops. Throughout most of the day, the Russians kept a safe distance from the Guard, beyond the range of French muskets and bayonets, opting to pound the Young Guard with cannon fire from a distance. This day, 17 November, might be remembered as the bloodiest in the Young Guard’s history. The many wounded soldiers were left behind and perished in the snow.

The retreat of the Young Guard did not end upon their return to Krasny. Mortier and Davout, vigilant of the possibility of Kutuzov launching an attack, joined the hurried procession of troops, crowds, and wagons heading towards Lyady. Only a feeble rearguard, led by General Friederichs, remained to hold Krasny.

Napoleon’s retreat

Before noon, Napoleon, accompanied by the stalwart Old Guard, followed by the remnants of the I Corps, commenced their westward departure from Krasny.[127] The road leading to Lyady quickly became congested with soldiers and their cumbersome wagons. Alongside them, a multitude of civilians, fugitives, and stragglers preceded the retreating French troops.[128] According to Guillaume Peyrusse there was no order. One could not find any trace of discipline.[129]

Just outside Krasny, Davout’s forces fell into an ambush set by the small detachments of Ozharovsky and Rosen dealing a severe blow to his rearguard. According to Buturlin they allowed Napoleon to pass but Davout was cut off.[130] Chaos ensued, with exploding grapeshot, overturned wagons, carriages careening uncontrollably, and panicked mobs of fugitives. Nevertheless, the Red Lancers under Colbert and Latour-Maubourg managed to force the Russians aside.[131] A large corps of Spanish voltigeurs (Old Guard) was ordered to attack.[132] The Guard’s strategic maneuver was intensified by Napoleon’s personal presence, but it came at a cost as he burnt his chancery and archive.[q]

After marching for about an hour, he gathered the Old Guard and formed them into a square. Dismounting, because the road – as smooth as a mirror and covered with snow – was too slippery for the horses,[134] Napoleon addressed them: “Grenadiers of my Guard, you bear witness to the disarray of my army.”[135] With his birch walking stick in hand, Napoleon placed himself at the forefront of his Old Guard. Although the temperature rose, it did not stop snowing.[136]

Kutuzov delays the pursuit

Despite the Russian eagerness to pursue the retreating French and launch an assault on Krasny, Kutuzov exercised caution, resulting in several hours of delay.[r]

At 2:00 p.m., confident that the French were in full retreat and not preparing to resist, Kutuzov finally gave the green light to Tormasov to execute his westward enveloping movement. Because of the snow Tormasov was not able to move quickly. Trying to establish a defensive position across a wide valley and obstructing the bridge at Dobraya. However, by the time Tormasov reached his intended location, it was too late in the afternoon to encircle and crush Davout’s corps.[138] According to Dutch officer Van Dedem, a part of the Grande Armee was granted free passage to Orsha,[139] leaving the entire army surprised by the Russians’ unexpected complacency.[140][122]

Around 3:00 p.m., Golitsyn’s troops launched a powerful assault on Krasny, and Friederichs’ rearguard yielded to the intense pressure and withdrew from the town. By nightfall, Golitsyn’s troops had seized control of the town and its environs. The enemy solidified its position at the hilltop and awaited for Ney,[141] whom Napoleon was reluctantly forced to abandon to its fate.[142] The Russian generals considered Ney as an easy prey.[143]

18 November: the decimation of Ney’s III Corps

Ney’s III Corps was designated as the rearguard, initially slated to depart Smolensk by 17 November. However, Ney’s attempt to destroy the rampart, guns and ammunition seemed to yield limited success due to the rainy weather.[t] He departed Smolensk with approximately six guns, 3,000 troops and a squadron of 300 horses, leaving behind as few French as possible.[145][146] Around 3:00 a.m. on 18 November, Ney’s Corps set out from Korytnya,[147] aiming for Krasny where Miloradovich had positioned his troops atop a hill, overlooking the gully containing the Losvinka stream.[148] On this day, thawing conditions, thick fog, and light rain resulted in the dreaded rasputitsa, creating treacherous icy surfaces as the evening advanced. Unaware of the Grande Armée‘s departure from Krasny, Ney remained oblivious to the impending danger near the gully. Around 3:00 p.m., Ney’s advance guard appeared at the Losvinka and briefly managed to reach the top before being repelled to the other side of ravine.[149][150] In Ney’s perspective, Davout still lingered behind Miloradovich’s columns within Krasny, further influencing his decisions. Disregarding a Russian offer for an honorable surrender, Ney courageously aimed to force his way through the combined enemy forces. Although the determined French soldiers breached the initial Russian infantry lines, the third line proved impenetrable.[113] At a crucial juncture, Nikolay Raevsky launched a fierce counterattack. Ney’s troops found themselves surrounded atop the hill, causing immense disorder and leading many to surrender.[u] The pivotal moment was narrated by the English General (in Russian service) Sir Robert Wilson:

Forty pieces of cannon loaded with grape, simultaneously on the instant, vomited their flames and poured their deadly shower on the assailants.

The survivors intrepidly rushed forward with desperate energy—part reached the crest of the hill, and almost touched the batteries. The Russians most in advance, shouting their “huzza,” sprang forward with fixed bayonets, and without firing a musket. A sanguinary but short struggle ensued: the enemy could not maintain their footing, and were driven headlong down the ravine. The Hulans of the Guard at the same time charged, swept through the shattered ranks, and captured an eagle.

The brow and sides of the hill were covered with dead and dying, all the Russian arms were dripping with gore, and the wounded, as they lay bleeding and shivering on the snow, called for “death,” as the greatest mercy that could be ministered in their hopeless state.[148]

Ney suffered more than half of his forces’ losses, with nearly all the cavalry and all but two artillery pieces vanishing.[151] The devastating defeat of the III Corps prompted Miloradovich to offer Ney another opportunity for an honorable surrender.[152] In the early evening, Ney chose to withdraw with his remaining troops.[153][154] Following the advise of colonel Pelet he maneuvered around the Russian forces at Mankovo, tracing the Losvinka’s path for several hours. By 9 p.m., they reached the desolate Syrokorene, located about 13 km north. There, they encountered a reserve of red beets, which they prepared for sustenance. At some point during the night, Ney learned of the impending threat by Denisov.[155] Amidst the darkness, he opted for a daring crossing of the Dnieper, purportedly between the remote hamlets of Alekseyevka, Varechki or Gusino. These spots boasted shallow river points but nearly vertical slopes.[156] Sappers employed logs and planks to create makeshift crossings over the ice. One by one, but not without significant losses, they managed, leaving two guns, part of the detachment and wounded who could not continue.[157][v] Ney’s men enduring the crossing on all fours,[158] with the elements and the Cossacks reduced their ranks to a mere 800 or 900 resolute soldiers.[159][160][161]

Ney made an audacious decision to lead everyone to the Dnieper, hoping to cross to the opposite bank on the ice. His choice left soldiers and officers alike astonished. Despite the incredulous gazes, Ney declared that if no one supported him, he would go alone, and the soldiers knew he was not making empty threats. When the fortunate few reached the opposite shore and believed themselves saved, they had to climb yet another steep slope to reach the shore, resulting in many falling back onto the ice. Of the three thousand soldiers who accompanied Ney, 2,200 drowned during the crossing.[162][163][164][165][w]

In the ensuing two days, Ney’s valiant band defended against Cossack assaults as they traversed 90 km westward along the river, navigating swamps and forests in their search for the French army. Ney maintained his defiance, rejecting surrender as Platov’s thousands of Cossacks pursued them halfway the river’s right bank.[166][167][168] Covered with snow, the morale of the French soldiers shattered, with surrender becoming a contemplation for some. Escaping Miloradovitch, only to face capture by Hetman Platov, seemed an ironic twist.[152] The French army was yet to reach the borders of the Russian Empire. On 20 November, at three in the morning, Ney and Beauharnais were reunited near Orsha, an event that revitalized the demoralized French troops, offering an emotional uplift akin to a triumphant victory.[147] Ney’s unwavering courage earned him the moniker “Bravest of the Brave” from Napoleon himself.

Correspondance by Napoleon

On 18 November Napoleon wrote a letter to Maret from Dubrowna:

Since the last letter I wrote to you, our situation has worsened. Severe frosts and temperatures as low as 16 degrees have caused the death of almost all our horses, around 30,000 in total. We were forced to destroy over 300 artillery pieces and a vast quantity of wagons. The cold has significantly increased the isolation of our men. The Cossacks have taken advantage of the complete ineffectiveness of our cavalry and artillery to trouble us and sever our communications. This makes me quite concerned about Marshal Ney, who stayed behind with 3,000 men to blow up Smolensk.

Nevertheless, a few days of rest, good food, and above all, horses and artillery supplies will restore us. But the enemy has the advantage over us in terms of experience and skill in maneuvering on ice, which gives them immense advantages during winter. A wagon or a piece of artillery that we cannot transport across the smallest ravine without losing 12 to 15 horses and 12 to 15 hours can be swiftly taken by them, thanks to specially made skates and equipment, quicker than if there were no ice.[169]

On 7 January 1813 he wrote Francis II, Holy Roman Emperor, his father-in-law, from Paris:

The story of the Krasnoye affair, where I was said to have retired at a gallop, is a flat fabrication. The so-called Viceroy affair is false. It’s true that from November 7th to the 16th, with the thermometer falling to 18 and even 22 degrees, 30,000 of my cavalry and artillery horses died; I abandoned several thousand ambulance wagons and baggage cars for lack of horses. The roads were covered in ice. In this terrible cold storm, the bivouac became unbearable for my people; many moved away in the evening in search of houses and shelter; I had no cavalry left to protect them. The Cossacks picked up several thousand.[170]

Summary of results

Krasnoi’s portrayal in historical literature offers contrasting perspectives. Older, more traditional texts focus solely on the Imperial Guard’s actions on November 17, presenting the encounter as a French victory. These accounts even go so far as to suggest a major combat and a Russian retreat. Chandler’s account echoes this older Bonapartist summary of the battle.[x] On the other hand, the latest narratives of the event by Riehn, Cate, and Smith view it as an incomplete Russian triumph over the Grande Armée. Napoleon made a great mistake, because the enemy was not following upon his rear, but moving along a lateral road.[22] Kutuzov had cut off Napoleon and wiped out Davout.[173]

The decision to divide into columns proved catastrophic, resulting in heavy defeats for the corps of Eugene, Davout and Ney throughout the four days of relentless combat.[6] The Russians captured a significant number of prisoners, including several generals and 300 officers,[174][175][y] while the Grande Armée was forced to abandon most of its remaining artillery and baggage train.[6][177]

The overall French losses in the Krasny skirmishes are estimated to range between 6,000, 13,000 and 15,000 killed; 1,200 wounded were treated by Larrey,[178] with an additional 26,000 captured by the Russians.[179][z] Almost all of the French prisoners were stragglers.[13] Many of these captives were transported to Tambov and Smolensk. The French also forfeited about 230 artillery pieces, half of which were abandoned, along with a significant portion of their supply train and cavalry.[13] Russian casualties, in contrast, are estimated at no more than 5,000 killed and wounded. Adam Zamoyski, following Buturlin is another opinion: between Maloyaroslavets and Krasny, Kutuzov had lost 30,000 men, and as many again had fallen behind, leaving him with only 26,500 available for action.[180][181]

The Battle of Krasnoe, which some military writers call a three-day battle, can only justly be described as a three-day search for hungry, half-naked Frenchmen; such trophies might have been the pride of insignificant detachments like mine, but not of the main army. Whole crowds of Frenchmen, at the mere appearance of our small detachments on the high road, hastily threw down their weapons.[182]

For a couple of days, French soldiers faced dire scarcity of sustenance and endured temperatures ranging from -12 to -25°C (-13 °F), along with strong winds, an abondance of snow and the discomfort of wet feet during thaw. The staff received delayed reports, and their orders either arrived too late or failed to reach them altogether.[93][aa]

This was the last action which the French army had to sustain in gaining the advance of the Russians. The number of its men bearing arms was diminished perhaps by some 20,000; for it left Smolensk 45,000 strong. A great part, however, of this total loss is to be placed to the account of fatigue, and the consequences of the actions, rather than the actions themselves.[183]

According to Minard’s map, around 24,000 men reached Orsha. The Vth corps comprising 5,150 men joined forces with 1,200 soldiers of the VIIIth corps under Junot, successfully reaching Orsha on 16 November.[184][ab] It is believed Napoleon entered Orsha with 6,000 guards, the remnants of 35,000, Eugene with 1,800 troops, the remains of 42,000 and Davout with 4,000, the remains of 70,000![186] Napoleon’s reunion with Ney, along with what was left of the III provided a glimmer of hope to rebuild his army around which to rally for the forthcoming Battle of Berezina and the War of the Sixth Coalition. According to Kutuzov:

I made sure your horses died of hunger on the route from Viazma to Smolensk. I knew by that that you would be forced to abandon to me what remained of your artillery in that latter city – and this happened just as I had predicted it would. As you left Smolensk, you could no longer fight against me with cavalry or artillery; my avant-garde was waiting for you near Krasny with fifty cannon. Since I wanted to destroy you without facing any resistance, I ordered them to fire only on the rear of the columns and only to send in the cavalry on disbanded corps. Your B. gave me more than I could ever have hoped for when he set a day’s interval between each army corp. Without my troops having to leave their positions, the guard and the three army corps which followed successively each left half of their soldiers. Those who escaped at Krasny will pass with difficulty at Orcha, and whatever happens, our dispositions are made on the Berezina such that, if my orders are followed precisely, there will be the end of the road for your army and its commander.[187][21]

Krasny unquestionably stands as a Russian victory, albeit a notably unsatisfactory one.Tsar Alexander I expressed disappointment in Kutuzov for not completely annihilating the remaining French forces. Yet, due to Kutuzov’s considerable popularity with the Russian aristocracy, Alexander bestowed upon him the victory title of Prince of Smolensk for his achievements in this battle.

The reasons behind Kutuzov’s decision not to obliterate the last vestiges of the French troops during the offensive remain unclear. General Nikolay Mikhnevich [ru], Russian military historian, suggested Kutuzov’s reluctance to jeopardize the lives of his exhausted and frostbitten troops. Mikhnevich cited Kutuzov’s own words, “All that [the French army] will collapse without me.”[188][ac] General Robert Wilson, the British liaison officer attached to the Russian Army, documented Kutuzov’s late 1812 statement,

I prefer giving my enemy a ‘pont d’or’ [golden bridge], as you call it, to receiving a ‘coup de collier’ [blow born of desperation]: besides, I will say, as I have told you before, that I am by no means sure that the destruction of Emperor Napoleon and his army would be of such benefit to the world; his succession would not fall to Russia or any other continental power, but to that which commands the sea, and whose domination would then be intolerable.[189]

Wilson strongly accused Kutuzov of deliberately releasing Napoleon from Russia.

In popular culture

Participants

- Louise Fusil

Louise Fusil, a French singer and actress, who was living in Russia for six years and returned with François Joseph Lefebvre, commanding the Old Guard, wrote:

When we came within sight of Krasnoy, the coachman told me that the horses couldn’t go any further. I dismounted, hoping to find headquarters in the town. It was getting light. I followed the path taken by the soldiers, and came to an extremely steep slope; it was like a mountain of ice that the soldiers slid down on their knees. Not wanting to do the same, I took a detour and arrived without accident. I asked an officer for headquarters. “I think he’s still here,” he told me, “but he won’t be for long, because the town is starting to burn”.[190]

At Krasny Fusil picked up an infant, left by its mother twice and took it to France.[191] Fusil may have been confused about the location. A story about soldiers – even Napoleon – sliding down the hill mention Lyadi.[192]

It is unclear what happened to Madame Aurore de Bursay, the leader of the French Theatre in Moscow. She sat in her theatre costume on top of a cannon.[193] According to Jean-François Boulart:

A young woman, a fugitive from Moscow, well-dressed and looking interesting, had just emerged from that brawl, riding on a donkey and struggling with her rather uncooperative mount when a cannonball shattered the poor animal’s jaw. I cannot express the sorrow I felt as I left that unfortunate woman, who was soon to become prey and probably a victim of the Cossacks.[95]

- Dominique Jean Larrey

The French surgeon Dominique Jean Larrey wrote:

It was a matter of urgent necessity that the army should resume its march after the battle, in order to avoid a new attack, and reach, as speedily as possible, those parts that were inhabited and provided with store-houses. All the troops, with some exceptions, were without arms, and in complete disorder. The guard, though reduced to less than half of its original number, was the only corps that had preserved its arms and good discipline. It was this body that protected the march of the isolated troops, and kept in awe those of the enemy, which incessantly pursued and harassed us. On our departure from Krasnoe, the temperature rose from ten to twelve degrees, and our sufferings from the cold were much diminished.[194]

Literature

Leo Tolstoy references the battle in his War and Peace. Throughout the novel, but particularly in this section, Tolstoy defends Kutuzov’s actions, arguing that he was less interested in the glory of routing Napoleon than in saving Russian soldiers and allowing the French to continue destroying themselves with a swift retreat.[195]: 635, 638

[Miloradovich] who was fond of parleys with the French, sent envoys demanding their surrender, wasted time, and did not do what he was ordered to do.

Towards evening – after much disputing and many mistakes made by generals who did not go to their proper places, and after adjutants had been sent about with counter orders – when it had become plain that the enemy was everywhere in flight and that there could and would be no battle, Kutuzov lef Krasnoe…

In 1812 and 1813 Kutuzov was openly accused of blundering. The Emperor was dissatisfied with him. … It is said that Kutuzov was a cunning court liar, frightened of the name of Napoleon and that by his blunders at Krasnoe and the Berezina, he deprived the Russian army of the glory of complete victory over the French.[196]

In the “Epilogue,” Tolstoy offers his thoughts on the historical events depicted in the novel and discusses his philosophy of history. The second part of the epilogue contains Tolstoy’s critique of all existing forms of mainstream history. He shares his perspective on the limitations of traditional historiography and questions the prevailing notion that history is solely shaped by the actions of great individuals. Instead, Tolstoy emphasizes the role of collective actions and the interconnectedness of various societal forces in shaping historical events.[197]

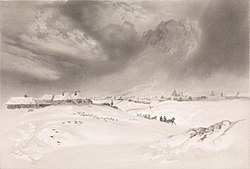

Paintings

Battle painters were busy catching the frequent acts of war during this campaign.[198]

- Covering Krasny, Jan Hoynck van Papendrecht pictured the last fight of the Dutch 3rd Regiment of the Garde impériale – of over 1000 men, only a few dozens were left when the Second Battle of Krasnoi was over.

- Peter von Hess rendered both battles, with summer colours in August and a grey winter atmosphere in November.

- Jean-Antoine-Siméon Fort focused on the troops of the French general Ricard.

- Jean-Charles Langlois, painter and soldier, captured the gloomy struggle against the enemy and the elements. The battle’s final hours also attracted attention:

- Adolphe Yvon showed Marshal Ney in rearguard action at the Losvinka, protecting the back of the advanced Napoleon Bonaparte, and, to the edification of his opponents,

- Napoleon’s hasty flight was visualized by Thomas Sutherland, likewise by John Masey Wright who added “disgraceful” to the title.

- Field Marshal Kutuzov was portrayed posthumously in 1813 in a serene pose by R.M. Volkov.

- Nikolay Samokish depicted a skirmish at close range in engraving technique.

Anniversaries

At the 100-year anniversary of the battle, Russian pride in the achievement was still strong. Memorials were erected at Borodino, Smolensk and Krasny, and Sytin’s Military Encyclopedia from 1913 included an illustrated article about the “Battle of Krasnoi”[199] with two sketches of the troop formations and copies of Peter von Hess’ battle paintings. Around 1931 the monument at Krasny was demolished, but reerected in 2012?[ad] In 2012, celebrating the 200th anniversary of the successful Battle of Krasnoi, the Moscow Mint issued a currency (5 rubles) with a special coinage.[202]

See also

Notes

- ^ For two/four days there was almost nothing to eat or drink and no bread at all.[20][21]

- ^ Cate, pp. 353–354, describes the devastating effects of frost on the Grande Armée at this time, including the estimation by Roguet that nearly 10,000 men, 30,000 horses froze to death in several consecutive nights.[27]

- ^ Napoleon’s northern flank began collapsing with Russian victories at the Second Battle of Polotsk (18–20 October) and the Battle of Chashniki (31 October), and the surrender of the massive French supply depot at Vitebsk (7 November). Napoleon’s operations to the south, which were guarded by the Austrian army in Volhynia, were compromised by a series of Russian maneuvers (21 September – 11 October) that forced the heavily outnumbered Austrian army to retreat into Poland without offering battle. This operational success enabled a sizeable force of Russians under Chichagov to begin an offensive (29 October) in the other direction — back to the east — to threaten Napoleon’s planned line of retreat near Minsk. In the Grande Armée’s main operational theater near Smolensk, a French defeat at Liakhovo (9 November) resulted in the surrender en masse of Augereau’s brigade to the Russians, while Platov’s Cossacks inflicted heavy losses on Eugène’s corps at the Vop (river) (9–10 November). Meanwhile, Cossack raids into Poland revealed widespread demoralization among the Poles, who were among Napoleon’s most important allies.

- ^ On 16 November the Franco-Polish garrison under Nikolai Oppeln-Bronikovsky, the governor of Minsk, surrendered to the Army of the Danube (1806–1812), which was another strategic and logistical disaster for Napoleon. It is generally believed to be led by Chichagov, but he arrived one day later than Charles de Lambert.[34][35]

- ^ According to Larrey, who was one of a few with a thermometer.[42]

- ^ On 16 November Zajączek and Dąbrowski reached Orsha, which means they were not involved in the skirmishes around Krasnoi.

- ^ Kutuzov apologized for not always knowing what to do due to lack of information and dependence on rumors.[53]

- ^ Erroneously called the Lossmina by most authors.

- ^ Chandler, Nicolson, and Napoleon’s biographer Felix Markham incorrectly state that Davidov was referring to the Guard’s skirmishing at Uvarovo on 17 November. But Davidov’s memoirs are highly specific regarding the date, time, and location of this occurrence;[65] there should be no doubt that it happened in the early afternoon of 15 November [O.S. 3 November] 1812 on the road 5km before Krasny.

- ^ There are several ravines from Smolensk on the road to Krasny, but the one at the Losvinka it is the deepest and steepest. The difference in height that had to be overcome is about 17m.[73]

- ^ The division led by Broussier suffered particularly heavy losses and was virtually wiped out within an hour. The division under Ornano was surrounded by Uvarov’s cavalry. His left column was cut off and surrendered.

- ^ Note that the details of the Guards’ troop composition, exact number of soldiers, high command, and exact direction of movement on this morning are superficially or confusingly described by most texts. The most up-to-date sources are from Zamoyski, Riehn, and Cate, and although these authors’ narratives are excellent and factually reliable, they do not address this action comprehensively. Segur’s description is richly detailed and probably veritable, but disjointed as a whole. The descriptions of this operation rendered by Chandler, Palmer, and Nicolson are contradictory, confusing, contain glaring factual errors, and should not be trusted by the reader. Roguet, sergeant Bourgogne and colonel Everts, who were present and Foord (1914) describe it well.

- ^ According to Bogdanovich, this happened when Napoleon decided to attack in the night, which seems more logical then in the early afternoon when Napoleon was leading the Imperial Guard out of Krasny.[101] Alison came to the same conclusion.[102] Tolstoy uses the phrase “J’ai assez fait l’Empereur, il est temps de faire le general” in: War and Peace, Vol. 3, Book 14, Chapter 18.

- ^ See Riehn, pp. 351–358, Cate, pp. 358–361, and Wilson, pp. 270–277, Tarle, pp. 364–368, and Parkinson, pp. 214–217, for eloquent, informative discussions of Kutuzov’s comportment at Krasny. Kutuzov’s possible motives for restraining his army at Krasny have been debated by historians for two centuries. The issue is especially inscrutable because of the Russian commander’s personality: he was more intelligent than most of his peers, and his manipulative, Machiavellian dealings in Russian military, social and political circles were well known. Some historians argue that Kutuzov wanted Napoleon to survive in order to counterbalance England’s dominance of international affairs, others argue that he did not want to jeopardize his place in posterity by risking open combat with Napoleon. Other explanations focus on Kutuzov’s advanced age—67 years old—his ill health and the fact that he was nearing death. Kutuzov’s proponents argue that he may have rightly reasoned that the Russian army’s combat capability at Krasny was not as formidable as was believed by other Russian generals and historians.

- ^ Next, Kutuzov, ordered Golitsyn to recapture the Losvinka. However, Golitsyn’s attack was met with a simultaneous counterattack by the 33rd Regiment (voltigeurs and tirailleurs) supported by the Guard’s Grenadiers (fusiliers).[111][115][116] Golitsyn responded by launching an attack with two regiments of cuirassiers (under Ilya Duka).[117] The Dutch Grenadiers on foot, supported by a Dutch regiment of Red Lancers and the cavalry of Latour-Maubourg, had to fall back under heavy Russian cannon fire after three hours.[87] The Grenadiers (under Ricard) sustained massive casualties and were forced out of a critical defensive position.[111] Roguet attempted to support the forces by attacking the Russian artillery batteries with Young Guards, but the offensive was thwarted by Russian grapeshot and cavalry charges.

- ^ Tormasov and Rosen were sent away at 11 in the morning.[122] Wilson indicates that Tormasov was not dispatched west until 2:00 p.m., well after Napoleon began his retreat from Krasny.[123]

- ^ It is unclear when and where this event took place, according to Lachouque this did happen on the 14th, the 16th or at Orsha.[133]

- ^ The sources conflict as to when the Russians advanced on Krasny. Rhiehn claims Miloradovich was not allowed to pursue the Young Guard until around 12:00 p.m., and that not until 3:00 p.m. did his troops attack Friederichs in the town,[137] Segur claims the Young Guard did not begin withdrawing until 2:00 p.m.

- ^ Ney was executed on 7 December 1815 for his support to Napoleon during the Hundred Days.

- ^ Ney was attacked by Platov in a suburb of the city. He seems to have left 5,000 wounded and women behind with a request by Larrey to take care of them.[144]

- ^ Tormassov and Miloradovich collected 12,000 prisoners on 18 November.

- ^ The Dniepr, 110 m wide and the depth could reach up to 2 m, was frozen since four days and ice broke at several places. When they reached the other bank, they had to climb twelve feet (3.7 m), a very steep icey slope.[158]

- ^ It is conceivable that Ney may have lost 2,200 men between Smolensk and the Dnieper. It’s implausible that all drowned; many were killed, some surrendered. Around 1,000 soldiers were captured during the pursuit.[8]

- ^ “The Russians, meanwhile, seemed in little hurry to get to serious grips with their adversaries. A great deal of skirmishing and minor actions took place at various points along the road, but nothing really serious happened until the 17th. By that date Napoleon had been at Krasnoe for two days, waiting for his extended column to close up. He was not altogether satisfied with the situation, however, as is shown by the dispatch of two regiments of the Young Guard to aid Eugène de Beauharnais‘s IVth Corps, which was held up by Davidov at Nikulino for much of the 16th before finding a way round the block through Jomini. Indeed, his anxiety to ensure that the main road should remain open induced Napoleon to order an attack against Kutuzov by the Guard on the morning of the 17th. At first he thought to entrust this operation to General Rapp, but then changed his mind and placed General Roguet of the Middle Guard in command. The operation was a complete success. The southbound French columns (16,000 strong) caught Kutuzov completely unawares, so accustomed had he become to the idea of a passive French opponent. The Russian partisan leader, Davydov, fancifully recorded that “The Guard with Napoleon passed through our Cossacks like a hundred-gun ship through a fishing fleet”, and in no time the Russian commander in chief was ordering his 35,000 men to retreat south. The Russians subsequently tried to misrepresent the outcome of the action, claiming that “Bonaparte commanded in person and made the most vigorous exertions, but in vain; he was obliged to flee the field of battle.” But this was flagrant propaganda. It was Kutuzov who had very much the worst of the encounter”.[172]

- ^ Louis Francois Lanchantin, Gijsbertus Martinus Cort Heyligers, Louis Alméras and François-Joseph Leguay?[176]

- ^ One notable prisoner was Jean Victor Poncelet, the future inventor of projective geometry.

- ^ From mid-August the Grande Armée had to deal with a lack of ink. Between 9/11 and 3/12 there were no bulletins. The latter, mentioning the return of the emperor to Paris put an abrupt end to uncertainty about the fate of the Grande Armee. The bulletin found eager public consumption.

- ^ This means these corps did not participate in the battle. Clausewitz and Chandler are mistaken. It seems the VIIIth corps ceased to exist not long after but the sources are limited; the Vth Corps ceased to exist after the battle at the Berezina.[185]

- ^ During the War of 1812, Nikolay Mikhnevich held the rank of lieutenant and served as an adjutant to Tormasov. Mikhnevich was present at various engagements, and his experiences during the war provided him with valuable insights into the military strategy and tactics employed by both sides.

- ^ In 1835, Nicholas I of Russia ordered to install 16 standard cast-iron monuments in the places of the most important battles of the Patriotic War of 1812. The architect of the projects of the monuments was Antonio Adamini. However, this plan was not fully realized. The first monuments were installed in Borodino, Smolensk and Kovno, then there were monuments in Maloyaroslavets and Krasny. But at the beginning of 1848 it became clear that the rest of the monuments lacked funds, and the program of installation of monuments had to be curtailed. Thus, seven of the planned sixteen monuments were installed. The monuments in Borodino, Maloyaroslavets, Krasny and Polotsk were blown up and melted down. By some miracle only one monument survived – in Smolensk.[200][201]

References

- ^ Chandler, David (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. p. 828. ISBN 978-0025236608. Retrieved 22 August 2023.

- ^ Riehn, pp. 344–345.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Riehn, p. 351.

- ^ Georges de Chambray (1825) Histoire de l’expédition de Russie: avec un atlas et trois vignettes, Volume 2, p. 434

- ^ Wilson, p. 266

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Lieven, p. 268.

- ^ Riehn, p. 359

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bogdanovich, p. 136

- ^ Foord, p. 343

- ^ Jump up to:a b Manuscript of 1812 Baron Fain

- ^ Foord, p. 348; the Russians claim 2,000 losses.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lieven, p. 267.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Foord, p. 343.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lieven, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Mémoires militaires du lieutenant général comte Roguet, p. 513

- ^ Smith, pp. 201–203

- ^ “М. Н. Покровский о войне 1812 года”. 17 August 1938.

- ^ Mémoires militaires du lieutenant général comte Roguet, p. 512-513

- ^ Bogdanovich, p. 137-138

- ^ Roguet, comte François (7 August 1865). “Mémoires militaires du lieutenant général comte Roguet (François) …” J. Dumaine – via Google Books, p. 526.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Lettres sur la guerre de Russie en 1812; sur la ville de Saint-Pétersbourg, les moeurs et les usages des habitants de la Russie et de la Pologne”. ÖNB Digital.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Antoine-Henri Jomini (1838) The Art of War, p. 235

- ^ Zamoyski, A. (2004) 1812: Napoleon’s fatal march on Moscow, p. 422, 427

- ^ Clausewitz, p. 212, 214

- ^ The Grande Armée’s implosion during the first stage of the retreat is summarized by Chandler (p. 823); Riehn (pp. 322, 335–337, 341); Cate (pp. 343–347) and Zamoyski (377–385).

- ^ Georges de Chambray (1825) Histoire de l’expédition de Russie: avec un atlas et trois vignettes, Volume 2, p. 436

- ^ Roguet, p. 511

- ^ Wilson, p. 253

- ^ Les bulletins françois, concernant la guerre en Russie, pendant l’année, 1812, p. 98

- ^ Georges de Chambray (1825) Histoire de l’expédition de Russie: avec un atlas et trois vignettes, Volume 2, p. 381

- ^ “Archived copy”. Archived from the original on 7 December 2006. Retrieved 2006-11-08.

- ^ Riehn, pp. 343–345.

- ^ Riehn, p. 349.

- ^ M. Bogdanovich (1863) Geschichte des Feldzuges im Jahre 1812, p. 220

- ^ Buturlin, p. 323-324

- ^ Riehn, pp. 349–350.

- ^ Georges de Chambray (1825) Histoire de l’expédition de Russie: avec un atlas et trois vignettes, Volume 2, p. 419

- ^ Die Deutschen in Russland 1812, p. 64

- ^ Jump up to:a b Napoléon Et la Grande Armée en Russie, Ou, Examen Critique de L’ouvrage de M. Le Comte Ph. de Ségur by Gaspard Baron Gourgaud (1825), p. 398

- ^ Riehn, pp. 350–351, discusses the Grande Armée’s order of march at this juncture and summarizes it as “an open invitation to disaster”.

- ^ Antoine-Henri Baron de Jomini in 1812-13, p. 68

- ^ Les mémoires de chirurgie militaire et campagne de D.J. Larrey, Volume 4, p 92

- ^ Mémoires militaires du lieutenant général comte Roguet, p. 510-511

- ^ Achilles Rose (2003) Napoleon’s Campaign in Russia Anno 1812 Medico-Historical, p. 34

- ^ Puybusque, L.G. de (1816) Lettres sur la guerre de Russie en 1812, p. 123

- ^ Bogdanovich, p. 105

- ^ Jump up to:a b Roguet, p. 518

- ^ Parkinson, p. 208; Riehn, pp. 337–338; Cate, p. 348.

- ^ Wilson, p. 265

- ^ Parkinson, pp. 213–214.

- ^ Bogdanovich (1861) Geschichte des vaterländischen Krieges 1812, p. 119 (History of the Great Patriotic War of 1812)

- ^ THE CAMPAIGN OF 1812 IN RUSSIA by CARL VON CLAUSEWITZ, p. 207

- ^ Bogdanovich, p. 138-139

- ^ Foord, p. 334

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Campagne et captivité en Russie, extraits des mémoires inédits du géneral-major H.P. Everts, traduits par M.E. Jordens” Carnet de la Sabretache, 1901, p. 698

- ^ [1] [2] [3] Recent photos by Elena Minina (2023), Smolensk

- ^ Cate, p. 358; Riehn, pp. 351–352.

- ^ Diary of partisan actions in 1812 by Davydov Denis Vasilyevich

- ^ Puybusque, L.G. de (1816) Lettres sur la guerre de Russie en 1812, p. 147

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wilson, p. 267

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wilson, p. 272

- ^ Jump up to:a b Riehn, p. 352.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Segur, p. 202.

- ^ In: The Service Of The Tsar Against Napoleon. The Memoirs of Denis Davidov, p. 142-143

- ^ Diary of partisan actions in 1812, p. 21

- ^ Puybusque, L.G. de (1816) Lettres sur la guerre de Russie en 1812, p. 128

- ^ Cate, p. 358.

- ^ Mémoires du général Rapp, p. 252

- ^ Cate (p. 359); Segur (pp. 199–201). David Chandler and many other historians confuse this night attack by the Young Guard against Ozharovsky on 15/16 November with the Imperial Guard’s feint against the Russian center on the morning of 17 November. Chandler et al. are in error on this count.

- ^ Memoirs of sergeant Bourgogne, p. 110-115

- ^ Foord, p. 338

- ^ MÉMOIRES MILITAIRES DU GÉNÉRAL BON BOULART SUR LES GUERRES DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE ET DE L’EMPIRE, p. 270-271

- ^ Smolensk topographic map

- ^ Adam Zamoysky (2004) Moscow 1812, p. 421

- ^ Buturlin, p. 209

- ^ Foord, p. 341

- ^ Mémoires militaires du lieutenant général comte Roguet, p. 514

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wilson, p. 268

- ^ Jump up to:a b D. Buturlin (1824) Histoire militaire de la campagne de Russie en 1812, p. 213[permanent dead link]

- ^ THE CAMPAIGN OF 1812 IN RUSSIA by CARL VON CLAUSEWITZ, p. 77-79

- ^ General Robert Wilson: Narrative of events during the Invasion of Russia by Napoleon Bonaparte, and the Retreat of the French Army, 1812, p. 269 access-date=14 February 2021

- ^ Bogdanovich, p. 112

- ^ Rzewski V.S. & V.A. Chudinov Russian “members” of the French revolution // French Yearbook 2010: Sources of the history of the French revolution of the XVIII century and the era of Napoleon. M.C. 6-45.

- ^ Moscow 1812: Napoleon’s Fatal March, p. 519

- ^ Wilson, p. 271

- ^ History of Europe (from 1789 to 1815). Volume 10, p. 79 by sir Archibald Alison (1855)

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Nafziger, George F. (7 August 1988). “Napoleon’s invasion of Russia”. Novato, CA : Presidio Press – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Napoléon Et la Grande Armée en Russie, Ou, Examen Critique de L’ouvrage de M. Le Comte Ph. de Ségur by Gaspard Baron Gourgaud (1825), p. 403-404

- ^ Wilson, p. 269.

- ^ Segur, p. 421.

- ^ Adam Zamoysky (2004) Moscow 1812, p. 422

- ^ Wilson, p. 274.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “1812 : eyewitness accounts of Napoleon’s defeat in Russia”. London : Readers Union : Macmillan. 7 August 1967 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Roguet, p. 516

- ^ Jump up to:a b MÉMOIRES MILITAIRES DU GÉNÉRAL BON BOULART SUR LES GUERRES DE LA RÉPUBLIQUE ET DE L’EMPIRE, p. 273

- ^ Jump up to:a b Caulaincourt, p. 219.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Caulaincourt, p. 220.

- ^ Alison’s map (1855) in higher resolution

- ^ Roguet, p. 518; 5,000 men under Napoleon, 6,000 under Mortier = 11,000

- ^ Bourgogne, Adrien (7 August 1910). Mémoires du sergent Bourgogne. Hachette (Paris). pp. 95–125, 118.

- ^ Bogdanovich, p. 120

- ^ History of Europe (from 1789 to 1815). Volume 10, p. 80 by sir Archibald Alison (1855)

- ^ “ВЭ/ДО/Красный — Викитека”.

- ^ Foord, p. 336-337

- ^ Wilson, p. 269

- ^ F.H.A. Sabron (1910) Geschiedenis van het 33ste Regiment Lichte Infanterie (Het Oud-Hollandsche 3de Regiment Jagers) onder Keizer Napoleon I, p. 104. Koninklijke Militaire Academie, Breda

- ^ Bogdanovich, p. 114-117

- ^ Human voices from the Russian campaign of 1812 by Arthur Chuquet (1912)

- ^ “Siméon Jean Antoine Fort | La Division Ricard au combat de Krasnoe le 18 novembre 1812, 9 h. du matin | Images d’Art”.

- ^ D. Buturlin (1824) Histoire militaire de la campagne de Russie en 1812, p. 217

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Wilson, p. 270.

- ^ D. Buturlin (1824) Histoire militaire de la campagne de Russie en 1812, p. 217

- ^ Jump up to:a b Cate, p. 361.

- ^ Foord, p. 339

- ^ Memoirs of sergeant Bourgogne, p. 118

- ^ Adam Zamoysky (2004) Moscow 1812, p. 423

- ^ Foord, p. 340

- ^ F.H.A. Sabron (1910) Geschiedenis van het 33ste Regiment Lichte Infanterie (Het Oud-Hollandsche 3de Regiment Jagers) onder Keizer Napoleon I, p. 110. Koninklijke Militaire Academie, Breda

- ^ Carnets et journal sur la campagne de Russie : extraits du Carnet de La Sabretache, années 1901-1902-1906-1912. Baron Jean Jacques Germain Pelet; M.E. Jordens; Guillaume Bonnet; Henri-Pierre Everts. Paris : Librairie Historique F. Teissèdre, 1997, p. 698-699.

- ^ THE CAMPAIGN OF 1812 IN RUSSIA by CARL VON CLAUSEWITZ, p. 79

- ^ Georges de Chambray (1825) Histoire de l’expédition de Russie: avec un atlas et trois vignettes, Volume 2, p. 450

- ^ Jump up to:a b Buturlin, p. 221

- ^ Wilson, p. 273

- ^ Segur, p. 204

- ^ Segur, p. 205; Bourgogne, p. 119.

- ^ Antoine-Henri Baron de Jomini in 1812-13, p. 69

- ^ Bourgogne, p. 249; Roguet, p. 521

- ^ Zamoyski, pp. 422–423.

- ^ Antoine-Henri Baron de Jomini in 1812-13, p. 70

- ^ Buturlin, p. 222-224

- ^ Wilson, pp. 273–274.

- ^ Mémoires du général Rapp (1823), p. 254

- ^ The Anatomy Of Glory; Napoleon And His Guard, A Study In Leadership by Henri Lachouque

- ^ Jakob Walter A German Conscript with Napoleon. 1938. p. 61. at the Internet Archive

- ^ Wilson, p. 283

- ^ Les mémoires de chirurgie militaire et campagne de D.J. Larrey, Volume 4, p 96

- ^ Riehn, p. 355

- ^ Wilson, p. 273.

- ^ Wilson, pl. 276

- ^ Dedem van Gelder, A.B. (1900) Mémoires du général baron Dedem de Gelder (1774–1825). Un général hollandais sous le premier empire, p. 283

- ^ “INS Scholarship 1997: Davout & Napoleon: A Study in Their Personal Relationship”. www.napoleon-series.org.

- ^ Lieven, p. 268

- ^ Zamoyski, p. 427

- ^ Zamoyski, p. 426

- ^ CG12 – 32051. – Au Maréchal Berthier, Major Général De La Grande Armée

- ^ “The Project Gutenberg eBook of Histoire de Napoléon et de la Grande-armée pendant l’année 1812; Tome II, by M. le général comte de Ségur”. www.gutenberg.org.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Fezensac, Raymond-Aymery-Philippe-Joseph de Montesquiou (7 August 1970). “The Russian campaign, 1812”. Athens : University of Georgia Press – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Wilson, p. 278.

- ^ D. Buturlin (1824) Histoire militaire de la campagne de Russie en 1812, p. 226[permanent dead link]

- ^ Wilson, p. 278

- ^ Holzhausen, Paul (7 August 1912). “Die Deutschen in Russland, 1812, Leben und Leiden auf der Moskauer Herrfahrt”. Berlin Morawe & Scheffelt verlag – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Leadership by Inspiration: An Episode of Marshal Ney during the Russian Retreat By Wayne Hanley West Chester University of Pennsylvania” (PDF).

- ^ Les bulletins françois, concernant la guerre en Russie, pendant l’année, 1812, p. 99

- ^ Holzhausen, p. 74

- ^ Wilson, p. 280

- ^ [4] [5] [6] show photos of the Losvinka and Dniepr by Elena Minina, Smolensk

- ^ Atteridge, A. Hilliard (Andrew Hilliard) (7 August 1912). “The bravest of the brave, Michel Ney, marshal of France, duke of Elchingen, prince of the Moskowa 1769-1815”. London : Methuen & Co. – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “The real places of the crossing of Marshal Ney’s 3rd Corps on November 6/18 and how it took place”.

- ^ Raymond-Aymery-Philippe-Joseph de Montesquiou, duc de Fezensac (1849) The Russian campaign, 1812, p. 87

- ^ Rickard, J (26 June 2014), Second battle of Krasnyi, 15-18 November 1812, http://www.historyofwar.org/articles/battles_krasnyi_2nd.html

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (23 December 2009). A Global Chronology of Conflict: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East [6 volumes]: From the Ancient World to the Modern Middle East. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851096725 – via Google Books.

- ^ History of Europe (from 1789 to 1815). Volume 10, p. 79 by sir Archibald Alison (1855)

- ^ “А! – Маршалы Наполеона. Ней Мишель (1769-1815)”. adjudant.ru.

- ^ “Е.В. Тарле «Нашествие Наполеона на Россию»”. www.museum.ru.

- ^ Zamoyski, p. 429

- ^ Wilson, p. 277

- ^ Freytag, Jean David (18 July 1824). “Mémoires du général J.-D. Freytag, ancien commandant de Sinnamary et de Conamama, dans la Guyane Française: Contenant des détails sur les déportés du 18 fructidor, à la Guyane, la relation des principaux événemens qui se sont passés dans cette colonie pendant la Révolution, et un précis de la retraite effectuée par l’arrière-garde de l’armeee Française en Russie, ses voyages dans diverses parties de l’Amériue, l’histoire de son séjour parmi les Indiens de ce continent”. Nepveu – via Google Books.p, 170-173

- ^ Holzhausen, p. 76

- ^ CG12 – 32060. – À Maret, Ministre Des Relations Extérieures

- ^ CG13 – 32230. – À François II, Empereur d’Autriche

- ^ Two bullets to the head and an early winter: fate permits Kutuzov to defeat Napoleon at Moscow (2016)

- ^ Chandler, et al., p. 828

- ^ Zamoyski, p. 431

- ^ Wilson, 276

- ^ Bogdanovich (1861) History of the Great Patriotic War of 1812, p. 136

- ^ officiers tués et blessés, p. 22

- ^ Smith, pp. 201–203.

- ^ Les mémoires de chirurgie militaire et campagne de D.J. Larrey, Volume 4, p 93

- ^ Mémoires militaires du lieutenant général comte Roguet, p. 628

- ^ Zamoyski, p. 434

- ^ Buturlin, p. 235

- ^ Davidov, “Diary of partisan actions in 1812”

- ^ Clausewitz, p. 78

- ^ Briefe in die Heimath: Geschrieben während des Feldzuges 1812 in Russland by Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg, p. 260

- ^ THE CAMPAIGN OF 1812 IN RUSSIA by CARL VON CLAUSEWITZ, p. 77-79; Chandler (1966), p. 828

- ^ Digby Smith, p. 205

- ^ “Beyond Smolensk”. napoleon.org.

- ^ Михневич Н. Отечественная война 1812 г. // История русской армии, 1812—1864 гг.. — СПб.: Полигон, 2003. — С. 45—46.

- ^ Sir Robert Wilson, The French Invasion of Russia, Bridgnorth, 1996, p. 234.

- ^ Fusil, Louise. “Souvenirs d’une actrice (2/3)”. www.gutenberg.org.

- ^ Souvenirs D’une Actrice, vol 2

- ^ Antoine-Henri Baron de Jomini in 1812-13, p. 70

- ^ Un général hollandais sous le premier empire, p. 282

- ^ Surgical memoirs of the campaigns of Russia, Germany, and France by D.J. Larrey (1832), p. 57

- ^ Tolstoy, Leo (1949). War and Peace. Garden City: International Collectors Library.

- ^ Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace, Volume III, Book XV, Chapter IV, V. Chapter IV online by the Project Gutenberg Etext of War and Peace

- ^ “_319 – War and Peace”. 4 April 2016. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016.

- ^ Katharina Painsi (2013) Die Darstellung Des Napoleonischen Feldzuges Von 1812 in Der Russischen Malerei Des 19. Jahrhunderts

- ^ I. D. Sytin (1913). “Battle of Krasnoi”. Military Encyclopedia (in Russian). St. Petersburg.

- ^ Monument to the defenders of Smolensk in 1812