Recently I have gathered substantial information on Charles-Henri Sanson (1739–1806). He left school in 1753 and continued his studies with private tutors. The exact moment when he began assisting in executions is uncertain: it may have been in 1754, when his father was paralyzed, or in 1756, at the age of seventeen (Reising, 2024, p. 62).

Although his father still held the title of executioner, most of the actual work was performed by Charles-Henri, with the support of his step-grandfather François Prudhomme. In 1755 Parliament allowed him to substitute for his father but refused to grant him formal investiture. To his lasting shame, in 1766 he failed to decapitate his father’s former friend, the Comte de Lally, with a single stroke, thereby subjecting him to unnecessary suffering (Mémoires des Sanson, vol. III, p. …)

Sanson became the official royal executioner at the court of Versailles after the death of his father, Charles-Jean-Baptiste Sanson, in August 1778. Charles-Henri had six younger half-brothers—also executioners in different parts of France—and two sisters (Reising, 2024, p. 62). His father, known as Monsieur de Paris to distinguish him from his brothers, lived in the Marais near the church of Saint-Laurent (close to today’s Gare de l’Est).

Educated and musically gifted, Sanson played the violin and the cello in his leisure time. He often met with his close friend Tobias Schmidt, a respected German instrument maker who would later build the guillotine. Together they performed works by Christoph Willibald Gluck (Mémoires des Sanson, vol. III, pp. 396–397).

In the final days of 1789, Antoine-Joseph Gorsas accused Sanson in the Courrier de Paris of harboring a royalist printing press in his home. On 27 January 1790 he was tried before the police tribunal at the Hôtel de Ville but acquitted, after which Gorsas withdrew the charge. The defense speech was published as Plaidoyer prononcé au tribunal de police de l’Hôtel de Ville de Paris… (Paris, 1790; 2nd ed., Bibliothèque nationale de France).[https://www.europeana.eu/item/794/ark__12148_bpt6k11808523?utm_source=chatgpt.com][https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclopædia_Britannica/Sanson,_Charles_Henri] At the same time Sanson was also denounced as a royalist by Camille Desmoulins in Révolutions de France et de Brabant, no. 7 (pp. 306–307) (Goulard, Charles-Henri Sanson, Mercure de France, 1 Feb. 1951, pp. 262–263; Mémoires des Sanson, vol. III, p. 301). According to Charles-Henri himself, the Sanson family was not regarded as citoyens actifs.

A contemporary source summarized Sanson’s position as follows:

Français (original)

« Ils payent, disent-ils, comme les autres sujets du roi, les vingtièmes, la captation, les charges de ville et de police, la taxe des pauvres. Ils rendent le pain béni sur les paroisses ; ils sont enregistrés dans la garde nationale de leurs districts. Pourquoi donc les empêcherait-on de participer aux autres avantages dont jouissent les autres citoyens ? » (Le Petit Moniteur universel, 27 décembre 1874).

English (translation)

“They pay, they say, like the other subjects of the king: the vingtièmes, the captation, the city and police charges, the tax for the poor. They distribute the blessed bread in their parishes; they are registered in the National Guard of their districts. Why then should they be prevented from sharing in the other advantages enjoyed by other citizens?” (Le Petit Moniteur universel, 27 December 1874).

In September 1790, when the new revolutionary constitution was published, Sanson suggested stepping down in favor of his eldest son. The National Assembly, however, did not accept this proposal (Mémoires des Sanson, vol. III, p. …). He never joined the Jacobin Club, but sought recognition as a citoyen actif.

On 25 April 1792 the National Assembly authorized the first use of the guillotine on a living person. According to the Mémoires, Louis XVI himself was consulted and gave his opinion (Mémoires des Sanson, vol. III, p. 403).

Sanson appears to have been arrested on or shortly after 10 August 1792, but he was released on the 21st in order to carry out several more executions during a period of heightened crime. On 27 August his son Gabriel died tragically while executing Jean-Blaize Vimal, a counterfeiter of assignats, together with two accomplices: he slipped on the scaffold in a pool of blood and fell to his death (Gazette nationale ou le Moniteur universel, 21 January 1893; ).[History of the Guillotine, Wikisource]

During the September Massacres Sanson, along with two of his half-brothers—Charlemagne in Versailles and Louis-Martin in Tours and Auxerre—was arrested again. He offered his resignation to the revolutionary authorities, but it was refused.[All That’s Interesting, “Charles-Henri Sanson”]

Sanson also became noted for his clothing: he first wore blue, but switched to green after critics pointed out that blue was considered the color of the nobility.[AlternateHistory.com, “Strange History Collection”]

Under the law of 14 October 1791, all active citizens and their sons over the age of eighteen were required to enlist in the National Guard. Its duties were to maintain public order and, if necessary, to defend the territory in wartime. Active citizens in 1790 had to provide certificates proving their continuous enlistment since that time.

On 12 August 1792, the royal family was transferred to the Temple. On the same day, during elections for officers of the National Guard, my grandfather and father were appointed sergeants, while my great-uncle Charlemagne Sanson became a corporal. These offices obliged them to take a more active role in political events than they wished (Mémoires des Sanson, vol. III, p. 462).

Français (original)

En revanche, le décalage entre les sections et les bataillons était maintenu : ce n’est qu’au lendemain du 10 août 1792 que la correspondance entre les deux cadres devait être rétablie, les sections devenant « sections armées », tandis que la Garde nationale s’ouvrait aux anciens citoyens passifs.[Affiches de la Commune de Paris.]

English (translation)

However, the discrepancy between the sections and the battalions remained: it was only after 10 August 1792 that the correspondence between the two frameworks was restored, with the sections becoming “armed sections,” while the National Guard was opened to former passive citizens.

Français (original)

À Paris, dès le 13 août 1792, les commissaires des sections rétablirent la concordance entre les sections et les bataillons de la garde nationale, que la loi du 21 mai 1790 avait détruite. La loi du 19–21 août 1792 légalisa la réduction des soixante bataillons à quarante-huit ; ce qui correspondait au nombre des sections de la Commune.[Devenne Florence. La garde Nationale ; création et évolution (1789-août 1792). In: Annales historiques de la Révolution française, n°283, 1990. pp. 49-66. DOI : https://doi.org/10.3406/ahrf.1990.1411 www.persee.fr/doc/ahrf_0003-4436_1990_num_283_1_1411]

English (translation)

In Paris, as early as 13 August 1792, the commissioners of the sections restored the alignment between the sections and the battalions of the National Guard, which had been abolished by the law of 21 May 1790. The law of 19–21 August 1792 legalized the reduction of the sixty battalions to forty-eight, corresponding to the number of sections in the Commune (Devenne, 1990).

Français (original)

Auparavant l’état-major sortait d’une élection au troisième degré : les capitaines, lieutenants, sous-lieutenants et sergents des compagnies d’un même bataillon élisaient le commandant en chef, le second et l’adjudant de ce bataillon. Et ceux-ci élisaient ensuite, avec ceux des autres bataillons, le chef, l’adjudant et le sous-adjudant de chaque légion (Braesch, p. 93). Voir l’arrêté de la Commune du 16 août, qui réorganise la garde nationale. [Affiches de la Commune de Paris.]

English (translation)

Previously the staff officers were chosen through a three-tier election: the captains, lieutenants, sub-lieutenants and sergeants of the companies in a battalion elected the commander-in-chief, his deputy, and the adjutant of that battalion. These officers then elected, together with those from the other battalions, the commander, adjutant, and sub-adjutant of each legion (Braesch, p. 93). See also the decree of the Commune of 16 August, which reorganized the National Guard (Affiches de la Commune de Paris).

Français (original)

L’Assemblée des Représentants nomma les officiers de ces compagnies dès le 24 octobre [S. Lacroix, t. II, p. 476–477]

English (translation)

The Assembly of Representatives appointed the officers of these companies as early as 24 October (S. Lacroix, vol. II, pp. 476–477).

Charles-Henri’s son, Henri-Nicolas-Charles Sanson (1767–1840), served in a battalion of the National Guard assigned to assist at the execution of Louis XVI, positioned close to but not on the scaffold (Mémoires des Sanson, vol. III, p. 472). In total, around one thousand guards were present on the square (Gazette nationale ou le Moniteur universel, 21 January 1893, G. Lenotre).

A month later, Sanson sent a letter to Le Thermomètre du Jour providing details of the execution. He wrote:

“When the King stepped out of the carriage for the execution, we told him we had to remove his clothes. He resisted, saying we could execute him as he was, and even offered to cut his own hair.” (Mémoires des Sanson, vol. III, p. 476)

According to Sanson, the condemned had to mount the scaffold barefoot, dressed only in a white shirt. Soon afterwards, reports circulated that relics of the execution were being sold:

“The buttons, scraps of clothing, and shirt of Louis Capet, as well as his hair, were collected and sold at very high prices to collectors. Executioner Sanson, accused of having participated in this new type of trade, has just written to journalists to clear his name on this matter; here are his words: I have just learned that there is a rumor circulating that I am selling or arranging the sale of Louis Capet’s hair. If any has been sold, this vile trade could only have been carried out by scoundrels. The truth is that I did not allow anyone from my household to take or remove even the slightest trace.”

Lenotre observed that such stories, though widely accepted, gave rise to “picturesque embellishments” and led some to believe that Sanson was consumed with remorse for having beheaded the King. “These are all errors,” he concluded: unpublished documents leave no doubt that Sanson only resigned on 13 Fructidor, Year III (30 August 1795). In his letter of resignation, Sanson stated:

“It has been forty-three years that I have served in this office. I am suffering from nephritic disease and can no longer continue my duties.” (Lenotre, pp. 148–149)

The Mémoires also indicate that during part of the Revolution, Charles-Henri Sanson kept a diary, recording not only the executions he carried out but also his personal reflections. He maintained this journal regularly only from late Brumaire Year II (November 1793), but he also left a vivid account of the execution of Charlotte Corday on 17 July 1793. This account, more elaborate than official trial records, retains its disjointed, unpolished style—yet it is precisely this simplicity that gives it its unique value.

For a long time it was believed that Charles-Henri Sanson had died in 1793 of grief (Dumas, La Presse littéraire, 14 June 1857), but this was a mistake. He was buried at Montmartre Cemetery on 4 July 1806 (Lenotre, p. 148; Find a Grave, Memorial ID 6754: accessed January 12, 2025). Even in 1911 the Encyclopædia Britannica noted that no official record of his death was known, and Henri Sanson was incorrectly presented as his immediate successor, a role he formally assumed only on 4 September 1795 (Le Gaulois, 19 January 1914).

After the insurrection of May–June 1793, the Convention decreed on 13 June that each department should appoint its own executioner.

Charles-Henri Sanson remained in office and supervised the execution of Charlotte Corday on 17 July. When his assistant François Le Gros committed a grave breach of decorum by striking Corday’s severed head, Sanson immediately reported the incident to Fouquier-Tinville; Le Gros was punished with imprisonment (Mémoires des Sanson, 1830, p. 25).

On 27 September 1793, Sanson’s brother Charlemagne received a certificate of civisme from the surveillance committee of the Faubourg du Nord (Feuille de Provins, 19 Dec. 1874). Although minor in itself, this detail is significant: it coincided with the beginning of the Terror, when such attestations of loyalty became essential for survival.

In the following months Charles-Henri, assisted by his son Henri and by Fermin, took part in the executions of Marie-Antoinette, Philippe Égalité, and the Girondin deputies on 31 October. That evening, however, Fouquier-Tinville accused Sanson himself of incivisme, a charge he indignantly rejected (Mémoires des Sanson, vol. IV).

Commentary. These details correct several persistent errors in the historiography. Contrary to claims that Sanson resigned or withdrew earlier, the sources show that he remained active well into the autumn of 1793, directly involved in some of the Revolution’s most significant executions.

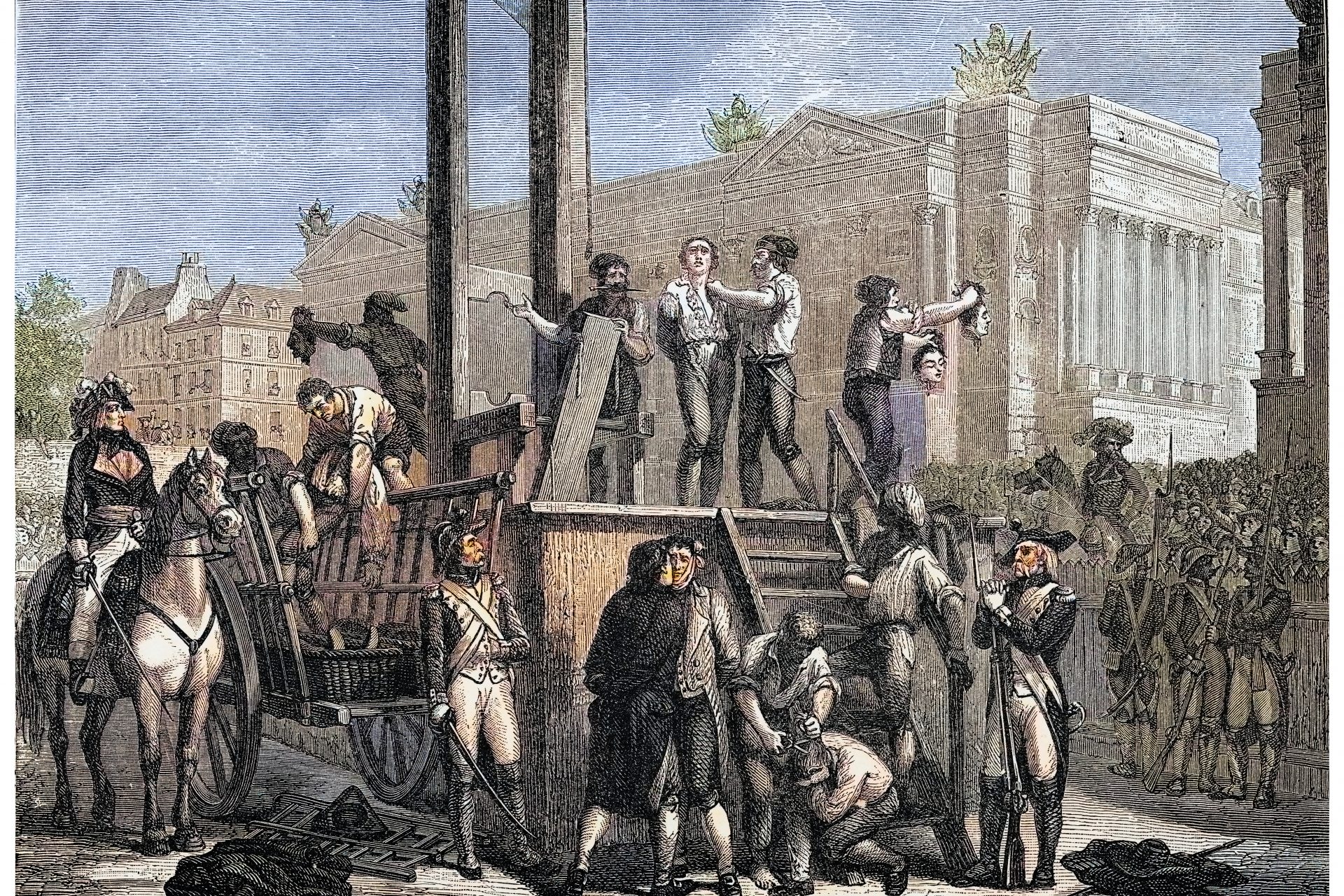

From the Mémoires: Henri Sanson supervised the removal of the bodies, which were thrown in pairs into the baskets waiting behind the guillotine. But after six heads had fallen, the baskets and the fallboard were so flooded with blood that the touch of this blood must have been much more terrible for the following ones than death itself. Charles Henri Sanson ordered two assistants to pour out several buckets of water and wash off the pieces with a sponge after each execution, p. ? Cesare Beccaria

He began by addressing the issue of citizenship, noting that although executioners were not legally recognized as citizens in France, they were still obliged to pay taxes like any other. He argued that the decree of 24 December 1789 failed to mention executioners, which led many to believe they were unfit for election or for holding civil or military office (Reising, 2024, p. 70).

Beccaria had argued that traitors to their country should be executed. Revolutionary leaders cited this principle to justify the punishment of those accused of counterrevolutionary activity. But Sanson interpreted Beccaria differently. In his diary entry of 2 February 1794 he expressed his growing aversion to the Revolution, criticizing judges and jurors for the sheer number of victims they sent to the guillotine. Executioners, he insisted, were meant to punish murderers and thieves—not citizens condemned for speaking out against their government and then put to death.

Yet Revolutionary leaders, too, claimed Beccaria’s authority, using his treatise to justify the ever-expanding executions during the Terror (Reising, 2024, pp. 76–77, 79, 83, 85).

Henri Sanson

Sanson, his brother Pierre–Claude, lieutenant, and Henri were involved in the events of 9 Thermidor. At that time Henri was “capitaine de la Garde Nationale de Paris puis Gendarmerie des Tribunaux; d’abord infanterie, depuis 31 (?) Octobre 1793 dans artillerie.” [Vol. V, p. 257; Vol VI, p. 143] [Mercure de France, 1 février 1949, p. 383] for four months. In December two commissionaires were sent to several areas, [Journal des débats et des décrets, 17 décembre 1793] where farmers and merchants, supported by priests, refused to pay paid with assignats, losing their value quicly. Henri served at Coulommiers until March and not until May, and returned to Paris.[Vol. V, p. 274]

He even got involved in politics by opposing the arrest of François Henriot. The suburbs of Saint Marceau, Saint Antoine and Saint Martin alone sent crews and guns to the square and the surrounding area of the town hall; and from a manuscript of my father it can be seen that many had been taken by surprise and did not even know that they were supporting an uprising. His brother and son Henri were arrested but released on 1 September 1794. It seems Henri was not involved in the execution of Robespierre, Saint-Just and all the others on 10 Thermidor, he executed Carrier, Fouquier-Tinville and Martial Herman.[p. 667-8]

Toulongeon, a former constituent who wrote in 1812, confirms that Robespierre received a pistol shot that shattered his chin cheek. There is reason, therefore, to suppose that an attempt at suicide on the part of Robespierre was only suspected; Louis Blanc shows it clearly in the notes which follow the seventh chapter of the tenth volume of his History of the Revolution. According to Louis Blanc, Méda would have entered the commune's consulting room long before Leonard Bourdon; when he recognized Robespierre, he would have wounded him with a pistol shot; all those present would have fled, and with a pistol shot he would have hit the shoulder of a man who was carrying Couthon away on a dark staircase. I will add a statement to this succinct account of Mr. Louis Blanc, which, however modest it may be, has its value. Méda belongs to that gendarmerie of the Tribunal, which came into daily contact with my father through his service; but the reasons for his promotion were no secret to anyone, and at the time when the most reliable historians assumed an attempt at suicide on the part of Robespierre, my father was already telling me about the pistol shot of gendarme Méda, about the consequences that the same had had for him, and about the anger that his promotion had caused among his former comrades, most of whom were angry Robespierrists. Be that as it may, a quarter of an hour after Leonard Bourdon entered the meetinghouse, the state of affairs was almost exactly as Barère described it. Maximilian Robespierre lay on the ground, badly wounded and covered with blood; after the younger Robespierre had taken off his shoes and walked a distance along the wide carnies of the first floor by the townhouse, he threw himself down on the tips of the bayonets; Couthon, only slightly bruised, was carried by his friends to the quay, but left there by them; Henriot was in no better condition than his accomplices, he had not let justice be done to himself, as Barère put it : outraged by his cowardice, Coffinhal had rushed him out to a window leading to one of the inner courtyards, and he had fallen on a pile of broken glass; still completely stunned by his trap, he had dragged himself into an alley, where he was found only a few hours later. Saint Just, Payan, Lescot, Fleuriot were arrested. Coward, Coffinhal told his friend, you had answered me for your troop: and, with a vigorous arm, dragging him towards a balcony, he threw him into a sewer, from where he was pulled out alive, but covered in blood and filth.[Mémoires de l'exécuteur des hautes-oeuvres, p. 309]

Dans les derniers mois de 1829 ou les premiers mois de 1830, L’Héritier de l’Ain qui venait de donner avec un grand succès (d’argent) les Mémoires de Vidocq proposa au libraire Mame la publication des Mémoires de Sanson. L’affaire se conclut et Charles-Henry Sanson signa un traité par lequel il s’engageait à laisser mettre son nom sur les volumes et à fournir des documents et matériaux aux « teinturiers » acceptés par lui. [La Gazette, 25 novembre 1905]ChatGPT: Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850) was both Catholic and a royalist, which is evident in his work and personal beliefs. Although he did not live a strictly devout life, he valued the Catholic faith as a moral and social foundation in society. For Balzac, the Church was a stabilizing force amid the upheavals and chaos of his time, such as the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era. As a royalist, Balzac admired the monarchy and the traditional hierarchies associated with it. He saw the monarchy as a symbol of order and continuity during a period of rapid democratic and liberal changes. This is also reflected in his magnum opus, La Comédie Humaine, where he often writes nostalgically about the nobility, old values, and the disappearance of traditional structures. His political and religious convictions made him somewhat controversial in 19th-century Paris, which was increasingly influenced by revolutionary and liberal ideas. Nevertheless, he remained committed to his conservative ideals, setting him apart from many of his contemporaries.

Les explications circonstanciées de Marco de Saint-Hilaire rassurèrent pleinement Dutacq, et c’est ainsi (pie, six mois après, le 15 juin 1853, parut dans Le Pays, sous le nom de Balzac, un nouveau fragment des Mémoires de Sanson sous le titre de : Une exécution militaire, Scène de la vie militaire.[Mercure de France, 1 novembre 1950]

Henri Clément Sanson

His Mémoires, a reworked version of the apocryphal memoirs of his grandfather, were republished by Henri Clément Sanson in 1862 (Volume I, II, III), in 1863 (Volume IV, V, VI) and 1876 an abridged English translation. The 1862 edition contains no references to Robespierre. According to P. Bourdin, a publicist named d’Olbreuse may have edited about one-third of the text? According to G. Lenotre in La Guillotine et les Executeurs des Arrets Criminels pendant la Revolution. D`apres des documents inedits tires des Archives de l`Etat, on page 105-106 the first three of four chapters in Volume I were written by d’Olbreuse. Henri-Clément Sanson who lived at 31 bis Rue des Marais on the fourth floor (?) was visited by d’Olbreuse in 1860. [https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k57887298/f6.image/f1n388.pdf?download=1 p. 201-209] Nothing is known about this mysterious d’Olbreuse on internet, perhaps a misspelling or pseudonym? According to Lenotre Sanson kept his mouth “like a fish”; meanwhile 80,000 copies were sold. D’ Olbreuse received 5,000, Sanson 30,000 francs.

Philippe Bourdin, « Sept générations d’exécuteurs. Mémoires des bourreaux Sanson (1688–1847) », Annales historiques de la Révolution française [En ligne], 337 | juillet–septembre 2004, mis en ligne le 15 février 2006. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/ahrf/1561 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/ahrf.1561

male victims’ occupations were written down by Charles-Henri Sanson. The total number of victims from January 1793 to July 1794 in Paris was 2,587. The class rank with

the highest number of victims during the Reign of Terror in Paris was the lower middle

class with a total of 708 and they made up 27% of the victims. [Reising, Willa Carlyle, p. 43] “At the height of the Terror, Sanson and his assistants guillotined 300 men and women in three days, 1,300 in six weeks, and between 6 April 1793 and 29 July 1795, no fewer than 2,831 heads dropped into the baskets.[https://www.geriwalton.com/french-executioner-charles-henri-sanson/#_ftnref5] Regarding the number of executed in Paris, the figures from Emile Campardon’s work are a little different from those given by Sanson and Reising: Campardon counted 2791 capital sentences pronounced by the Revolutionary Court between March 10, 1793 and May 31, 1795.

Sources

- (en) Willa Carlyle Reising, Beccaria, the Executioner, and the French Revolution (Thèse de doctorat), Morgantown, West Virginia University, coll. « Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports », , 12609e éd. (lire en ligne)