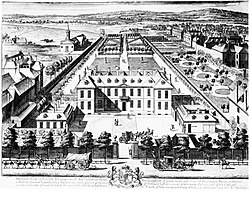

Amadigi di Gaula (HWV 11) is a “magic” opera in three acts, with music by George Frideric Handel. It was the fifth Italian opera that Handel wrote for an English theatre and the second he wrote for Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington composed during his stay at Burlington House in 1715. The opera about a damsel in distress is based on Amadis de Grèce, a French tragédie-lyrique by André Cardinal Destouches and Antoine Houdar de la Motte. Charles Burney maintained near the end of the eighteenth century, Amadigi contained “…more invention, variety and good composition, than in any one of the musical dramas of Handel which I have yet carefully and critically examined”.[1][2]

The opera received its first performance in London at the King’s Theatre in the Haymarket on 25 May 1715. Handel made prominent use of wind instruments, so the score is unusually colorful, and at points resembles the Water Music, which he composed only a few years later. Amadigi, written for a small cast, employs no voices lower than alto and it ends in a minor key. Exceptional care was lavished on the production. The opera was a success and received a known minimum of 17 further performances in London through 1717.

Composition history

The identity of the librettist is not known for certain.[3][4] Previous consensus had been that John Jacob Heidegger, who signed the dedication to Richard Boyle, 3rd Earl of Burlington was the author,[5] but more recent research has indicated that the librettist was more likely to be Giacomo Rossi, with Nicola Francesco Haym as a more probable candidate.[6] This libretto is an adaptation of a medieval Spanish knight-errantry epic Amadis de Gaula in which the King of Gaul, educated in Scotland, falls in love with and eventually marries Oriana, daughter of the King of England.

David Kimbell compared in detail the treatments of the story by Handel and Destouches.[7]

What interested Handel was the emotions and the sufferings of the four characters.[8] not the descriptive effects of his later “magic” operas. The sole preoccupation of each of the protagonists is to make the others fall in or out of love with them. Handel went deeper into their sentiments than he ever would again.[9]

In act 2 Amadigi addresses the Fountain of True Love in a long cavatina of the utmost sensuous beauty. This scene was famous originally for its spectacular effects. The “coup de theatre” then was the use of a real fountain spraying real water. The scene employed a large number of stage engineers and plumbers, among other things, such that the following newspaper announcement appeared on the day of the premiere: “whereas there is a great many Scenes and Machines to be mov’d in this Opera, which cannot be done if persons should stand upon the Stage (where they could not be without Danger), it is therefore hop’d no Body, even the Subscribers, will take ill that they must be deny’d Entrance on the Stage”.[10]

According to Winton Dean the quality of the score, especially the first two acts, is remarkably high, but it shows less careful organization than most of the later operas. He also states that the tonal design seems off balance. The conception of an opera as a coherent structural organism was slow to capture Handel’s imagination.[11] For five years he did not compose another opera.

The original manuscript of Amadigi has disappeared, along with ballet sections in the music. Only one edition of the libretto is known, dating from 1715. Two published editions of the opera exist, the Händelgesellschaft edition of 1874, and the first critical edition, by J. Merrill Knapp, which Bärenreiter published in 1971.[4] Dean has examined the history of various manuscripts which contain alternative selections for the score.[12]

The opera is scored for two recorders, two oboes, bassoon, trumpet, strings, and basso continuo (cello, lute, harpsichord).

The singer Elisabetta Pilotti-Schiavonetti in the role of Melissa, who specialised in playing sorceresses, and for whom Handel had written the similar parts of the witch-like Armida in Rinaldo and Medea in Teseo is distinguished in Handel’s music between her vengeful character and that of the other leading female part, the sweet Princess Oriana.[13]

Performance history

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere Cast, 25 May 1715 |

|---|---|---|

| Amadigi | alto castrato | Nicolo Grimaldi (“Nicolini”)[21] |

| Oriana | soprano | Anastasia Robinson[22] |

| Melissa | soprano | Elisabetta Pilotti-Schiavonetti[23] |

| Dardano | contralto | Diana Vico |

| Orgando | soprano | (unknown) |

Setting

Oriana was heiress to the throne of England. Amadis of Gaul is a prince born of a secret amour, educated in Scotland, reared as a knight, and serving devotedly the fair English princess Oriana. For her sake he contends against monsters and enchantments, and defends her father’s kingdom from an oppressor. Richard B. Beams wrote:

“The sorceress Melissa, infatuated with Amadigi, has imprisoned Oriana in a tower and both Amadigi and Dardano in her garden. After various deceptions, visions, and trials, the two lovers, Amadigi and Oriana, are finally united. Before then, Amadigi will slay Dardano, his companion turned rival, and Melissa, will stab herself finding her supernatural powers impotent against the power of love.”[1]

The plot ranges across the continent to Romania and Constantinople, and in the continuations as far as the Holy Land and the Cyclades. However, the romance’s geography cannot be mapped onto the “real” Europe: it contains just as many fantastic places as real ones.

“When the Spaniards first saw Mexico, they said to each other it was like the places of enchantment which were spoken of in the book of Amadis. This was in 1549.[25]

Historically, Amadís was very influential amongst the Spanish conquistadores. Bernal Diaz del Castillo mentioned the wonders of Amadís upon witnessing the wonders of the New World – and such place names as California and Patagonia come directly from the work.

Synopsis

Act 1

Amadigi, a Paladin, and Dardano, the Prince of Thrace, are both enamoured with Oriana, the daughter of the King of the Fortunate Isles. Oriana prefers Amadigi in her affections. Also attracted to Amadigi is the sorceress Melissa, who tries to capture Amadigi’s affections by various spells, pleadings and even threats. Amadigi confronts various spirits and furies, but rebuffs them at practically every turn. One particular vision at the “Fountain of True Love”, however, of Oriana courting Dardano upsets Amadigi to the point that he faints. Oriana sees Amadigi prostrate, and is about to stab herself with his sword when he awakens. He immediately berates her for her apparent betrayal of him, and in his turn tries to stab himself.

Act 2

Still alive, Amadigi continues to resist the advances of Melissa. Melissa then makes Dardano look like Amadigi, to deceive Oriana. Oriana follows Dardano, in the visage of Amadigi, to beg his pardon. Dardano exults in the attention of Oriana, and in an impulsive moment, challenges Amadigi to single combat. In the duel, Amadigi kills Dardano. Melissa accuses Oriana of stealing Amadigi from her, and calls upon dark spirits to assault Oriana, who resists all of Melissa’s incantations.

Dardano’s celebrated aria Pena tiranna io sento al core from Act 2 is notable for its prominent bassoon part and its chord sequence based on the circle of fifths or, rather, circle of fourths. The introduction is shown in score as one of the Baroque examples.

Act 3

Amadigi and Oriana have been imprisoned by Melissa. The two lovers are willing to sacrifice themselves for each other. Though desirous of revenge, Melissa cannot quite yet kill Amadigi, but torments him by prolonging his confinement in chains. Amadigi and Oriana ask Melissa for mercy. Melissa summons the ghost of Dardano to assist her in her revenge, but the ghost says that the gods are predisposed to protect Amadigi and Oriana, and that their trials are nearly done. Rejected on all levels, by the gods, the underworld spirits and Amadigi, Melissa takes her own life, with one final plea to Amadigi to feel a shade of pity for her. In the manner of a deus ex machina, Orgando, uncle of Oriana and a sorcerer himself, descends from the sky in a chariot and blesses the union of Amadigi and Oriana. A dance of shepherds and shepherdesses concludes the opera.[26]

Recordings

- Erato 2252 454902: Nathalie Stutzmann, Bernarda Fink, Eiddwhen Harrhy, Jennifer Smith; Les Musiciens du Louvre; Marc Minkowski, conductor[27][28]

- Naïve AM 133: Maria Riccarda Wesseling, Elena de la Merced, Sharon Rostorf-Zamir, Jordi Domènech; Al Ayre Español; Eduardo Lopez Banzo. Release Date: 26 February 2008

References

- Notes

- ^ Jump up to:a b Richard B. Beams, “Handel’s Amadigi di Gaula: Central City Opera Strikes Gold, July 2011″ on operaconbrio.com. Retrieved 18 June 2014

- ^ Charles Burney: A General History of Music: from the Earliest Ages to the Present Period. Vol. 4, London 1789, reprint: Cambridge University Press 2010, ISBN 978-1-1080-1642-1, p. 255.

- ^ Dean, Winton, “Handel’s Amadigi“, The Musical Times, April 1968, 109 (1502): pp. 324–327.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Crow, Todd, Review of “Hallische Händel Ausgabe. Ser. II: Opern; Band 8: Amadigi, opera seria in tre atti” (edition prepared by J. Merrill Knapp) (June 1973). Notes (2nd Ser.), 29(4): pp. 793–794.

- ^ “Amadis of Gaul”. Gutenberg.org. 1 January 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ Dean & Knapp, p. 274.

- ^ Kimbell, David R.B., “The Amadis Operas of Destouches and Handel”, Music & Letters, October 1968, 49 (4): pp. 329–346.

- ^ Dean & Knapp, p. 277.

- ^ Rouvière, O, “A musical map of the emotions”, p. 17, 2008 in booklet accompanying the recording by Al Ayre Español

- ^ Dean & Knapp, p. 287.

- ^ Dean & Knapp, p. 286.

- ^ Dean, Winton, “A New Source for Handel’s Amadigi“, Music & Letters, February 1991, 72 (1): pp. 27–37.

- ^ Dean, Winton. “Winton Dean on Teseo”. Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ Sadie, Stanley (ed) (1992). The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, vol. 1 pp. 102–3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-522186-2.

- ^ “Handel:A Biographical Introduction”. GF Handel.org. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ “Warner (Music Canada) Gives the Gift of Music to Western”, 27 February 2003

- ^ MacMillan, Kyle (6 July 2011). “Central City Opera brings to life the long-lost, spectacular score from “Amadigi““. The Denver Post. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ Coghlan, Alexandra. “Handel Festival 2012”. The Arts Desk. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ^ Rhein, John von (7 November 2015). “Haymarket Opera showcases worthy Handel rarity ‘Amadigi‘“ (PDF). Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ^ Arden, Charles. “Amadigi, le Paladin de Haendel par Les Paladins de Correas à l’Athénée – Actualités – Ôlyrix”. Olyrix.com (in French).

- ^ He sang eight newly composed arias and a duet with each of the primadonna‘s

- ^ She was taken ill after the first performance and had to be replaced (by Caterina Galerati?) for the remaining five performances

- ^ Elisabetta Pilotti-Schiavonetti Biography – (d Hanover, 5 May 1742), Idaspe fedele, Rinaldo, Il pastor fido, Teseo, Amadigi, Antioco, Ambleto [1]

- ^ “Amadis of Gaul spainthenandnow”. Spainthenandnow.com. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ “Preface”. Donaldcorrell.com. Archived from the original on 6 October 2011. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- ^ “Handel House – Handel’s Operas: Amadigi di Gaula”. Handel and Hendrix. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- ^ Freeman-Attwood, Jonathan, “A Handelian Feast” (March 1992). The Musical Times, 133(1789): pp. 131–132.

- ^ “Handel – Amadigi di Gaula, opera, HWV 11”. Monova.org. 8 December 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2011.

- Cited sources

- Dean, Winton and Knapp, J. Merrill, Handel’s Operas, 1704–1726. Clarendon Press, 1987 ISBN 0-19-315219-3

External links

- Italian libretto.

- Italian libretto with contemporary English translation

- Amadigi di Gaula: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

![]()